A little over a year ago, folks attuned to such things might have caught wind of a news story involving Red Wolves, Coyotes, and Galveston Island right here in Texas. The exciting part of this report was the mention of Red Wolves—these wild canids were thought to have become extinct in the wild early in the 1980s, and the possible discovery of a population of free-ranging Red Wolves living in Texas would be big news for sure.

The Galveston Island Story

The story of the Galveston Island canids began in December 2018 with release of a paper written by a team of researchers lead by Princeton University biologists. The authors had developed evidence, through sample analysis, indicating that there is a populations of wild canids living on the island that have an exciting percentage of Red Wolf genetic code.

In the popular press the story was reported with a lot of zeal and more than a few exaggerations. It was a story that was ripe for misunderstanding. It was a story that deserved a closer look…

Red Wolves in North America

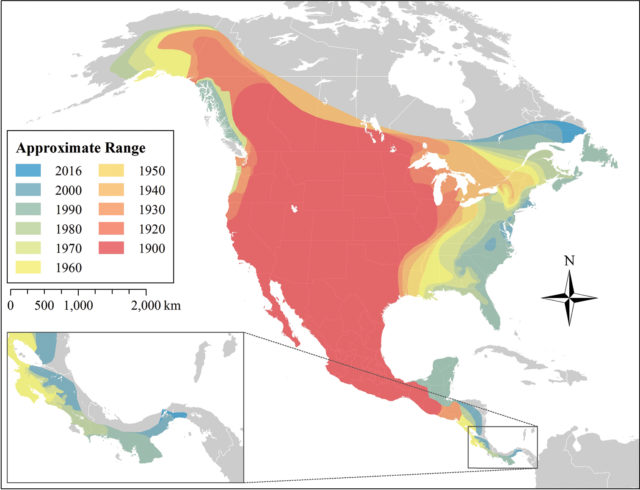

Historically, Red Wolves were found all across the southern United States, but It has been a century or more since Red Wolves have been common in Texas, or anywhere else in the lower 48. Decades of intensive predator eradication programs eliminated them from most all of their original range. Hybridization with Coyotes further threatened their numbers. From 1973 to 1980 the last few remaining Red Wolves were captured by scientists for inclusion in a captive breeding program, and the species was declared extinct in the wild—a managed expiration.

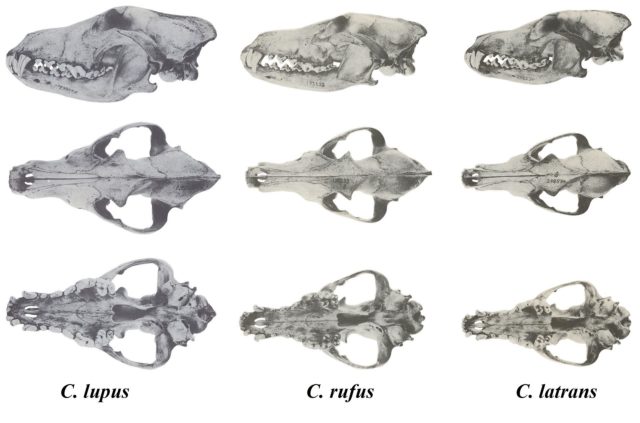

Morphologically, Red Wolves fall somewhere in size between Gray Wolves and Coyotes. Their behavior sits between the two as well—Red Wolves are reportedly more social than Coyotes, but less so than Gray Wolves.

Of the three species, Gray Wolves form the most cohesive social groups of 6 to 10 members. Referred to as packs, a strict social hierarchy is enforced among the members. They hunt cooperatively—a strategy that allows Gray Wolves to take on large and powerful prey animals.

Coyotes, on the other hand, defend territories as loose family groups of 3 to 6 individuals. They typically hunt small prey animals either alone or as pairs. Coyotes are highly adaptable, and can thrive in the presence of people—in both rural and urban environments.

Red Wolf behavior falls somewhere in between the Gray Wolf and Coyote. Red Wolves are said to form packs including 5 to 8 members, and will sometimes take on prey as large as White-tailed Deer or Feral Hogs. But they also feed readily on smaller animals, such as nutria or rabbits. Red Wolves tend to be shy and retiring. They are sensitive to human encroachment, and do not do well without a certain amount of isolation.

Picture from Wikipedia

but they typically hunt small game alone or in pairs

Are the Galveston Island Canids Red Wolves?

The team of biologists working on the Princeton paper analyzed genetic material from a pair of roadkill Galveston Island canids. The study refers to the two subject canids as Galveston Island 1 (GI-1) and Galveston Island 2 (GI-2). These two canids, as well as others in their family group, were selected for this analysis because of perceived physical similarities to Red Wolves.

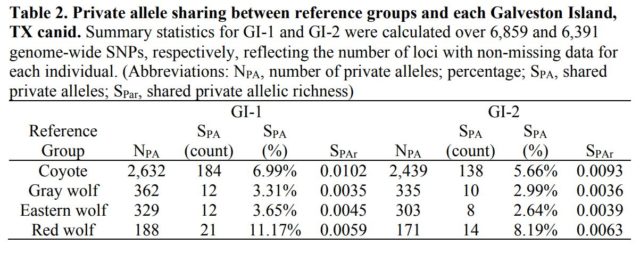

Genetic code from the two Galveston Island canids was compared to reference populations of Gray Wolves, Eastern Wolves, Coyotes, and Red Wolves. Sure enough, GI-1 and GI-2 were found to have some notable percentage of genetic code in common with all four of the reference groups—Gray Wolves, Eastern Wolves, Coyotes, and Red Wolves.

The key finding of this study, though, may be the identification of possible Red Wolf “ghost alleles” found in the genetic material of GI1 and GI2.

Ghost alleles are portions of genetic code that are unique to the Galveston Island canids—this is genetic code that was NOT found in the reference populations of Coyotes, Gray Wolves, Eastern Wolves, OR Red Wolves used in this study. The authors speculate that these “ghost alleles” may represent Red Wolf genetic code that is no longer found in the current Red Wolf population, because of the genetic bottleneck resulting from their near extinction.

But are these “ghost alleles” really from Red Wolves? Unfortunately, there is no way to be sure without identifying a reference population of Red Wolves that also possesses these alleles. Here’s how the authors describe the dilemma…

Overall, the GI canids carried 21 alleles that were absent from all reference populations…. It is possible that these alleles represent at least some of the genomic diversity in the historical wild red wolf population that was lost as the result of selecting 14 captive breeding founders from the wild, but this is speculation in the absence of documented historical red wolf samples.

The question then becomes, did the Princeton study determine that the Galveston Island canids are indeed Red Wolves?

To get straight to the point, the answer is no. Nowhere does the Princeton paper make the claim that the study animals on the island are actually Red Wolves… only that these canids are reservoirs of some subset of Red Wolf genetic code. Even more, the study ALSO determined that the two Galveston Island canids possess a small percentage of Gray Wolf and Eastern Wolf genetic code.

Altogether these findings do not mean that the Galveston Island canids are Red Wolves, anymore than they mean that GI-1 and GI-2 are Gray Wolves or Eastern Wolves. The canids on Galveston Island are Coyotes with some genetic evidence of a shared ancestry with Red Wolves, Gray Wolves, and Eastern Wolves. Here is how the Princeton paper presents its findings in this area…

some number of private alleles in common with each reference group species

Finally, it is important to recognize that the Princeton study makes no effort to describe how the shared genetic code or the ghost alleles express themselves in Galveston Island canids’ appearance and behavior—or if they even do.

Comparing Coyotes to Red Wolves

When compared to Coyotes, Red Wolves tend to be larger on average. Adult Red Wolves weigh anywhere from 36 to 76 pounds, while Coyotes typically fall in the range of 15 to 45 pounds. In length, Red Wolves measure from 53 to 63 inches, and Coyotes can be anywhere from 39 to 53 inches.

Red Wolves are considered trim and lanky, with long legs. The Red Wolf’s longer legs makes their tail appear shorter than that of a Coyote. Red Wolves have rounder skulls and short, broad muzzles when compared to Coyotes, which have longer, narrower snouts. Ear shapes also vary slightly between the two canids. And Red Wolves are often considered as having a more vivid coloration than Coyotes.

This illustration was designed to accentuate

the difference between these two canids.

Picture courtesy Wikipedia

The illustration above compares a Red Wolf to a Coyote. The photographs used in this comparison were carefully selected to accentuate the differences between the two animals. In truth, there is actually a great deal of variability in the appearance of Coyotes. Individual Coyotes can differ significantly from one to another. Further, Coyotes change appearance in dramatic ways from season to season, as their thick winter coats are molted for spring and summer.

It is not difficult to find pictures of Coyotes that closely resemble Red Wolves. Likewise, it is also not difficult to find images were the Coyotes look starkly different from what is typically thought of as a Red Wolf. See below for a few examples of Dallas/Fort Worth area Coyotes…

They typically appear smaller and leaner during the summer months.

This one was photographed in Dallas, Texas

What is a Red Wolf?

One issue that complicates matters significantly is the fact that no one is 100% certain what a Red Wolf actually is. There is even room to question whether the Red Wolf is a distinct species or not. There seems to be a couple of accepted possibilities. The animal we call the Red Wolf may actually be one of the following…

- A distinct species

- A recent Gray Wolf/Coyote hybrid

- An ancient Gray Wolf/ Coyote hybrid

- A distinct species/Coyote hybrid

Some studies even suggest that there is only one species of Wolf in North America—the Gray Wolf. All others—the Eastern Wolf, the Mexican Gray Wolf, and the Red Wolf—are simply Gray Wolf/Coyote hybrids. As you can see from the images and illustrations that follow, it is not difficult to image the Red Wolf as a Gray Wolf/Coyote mix…

Image from Untamed Science

Picture courtesy Wikipedia

Picture courtesy Wikimedia Commons

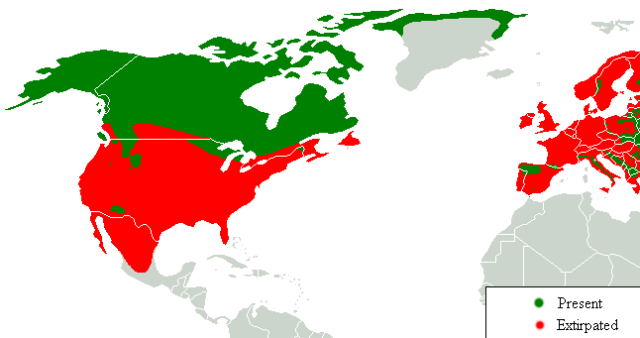

In North America, our medium and large canines (Gray Wolves, Eastern Wolves, Red Wolves, Dogs, and Coyotes) can interbreed and produce fertile offspring. Further, there is a good evidence that cross-breeding does sometimes occur when properly facilitated by circumstances. This intermixing makes the idea that North American wild canids share genetic code somewhat unremarkable.

As you can see in the range maps that follow, overlapping distribution would have provided for ample opportunities for intermixing in the past. There is a great deal to read about such matters. Wikipedia is a fine place to start: Canid Hybrids.

Map courtesy Wikipedia

Map courtesy Wikipedia

Red Wolves and Coyote are similar in size and behavior—much more so than either is with the Gray Wolf. This circumstance likely facilitates interbreeding between the two. In fact, Red Wolf-Coyote hybridization is well documented, and Red Wolves readily mate with Coyotes. The resulting genetic dilution has long been considered as one of the primary threats to the Red Wolf’s continued existence in the wild.

The idea that the Red Wolf may be a hybrid is one of the areas that the politics of conservation comes into play with this issue. Despite their dwindling numbers, Red Wolves are sometimes left off endangered species lists for the very reason that they considered hybrids by some organizations.

Revisiting the Galveston Island Story

The popular press gets excited about stories like the one from Galveston Island—sometimes a little too excited. Misleading articles can result, and retractions/corrections rarely see the light of day. People often come away from such stories with the wrong impression.

A good example of this type of misreporting can be found in the Texas Parks and Wildlife Magazine article covering the news of the Princeton study. Texas Parks and Wildlife Magazine is generally considered to be a reputable publication. It would be easy to assume the information they provide is well founded and reliable. But in their article covering the Galveston Island canids, the claim is made—a number of times—that the Galveston Island canids are half Red Wolf and half Coyote. This is a misleading assertion that significantly overstates what was actually revealed by the Princeton study.

Half-and-half implies that the Galveston Island canids are the immediate offspring of a pairing between a full-blooded Red Wolf and a full-blooded Coyote. This is obviously not possible, and the Princeton paper makes no such bold claim (there are no full-blooded wild Red Wolves in Texas). The researchers only report evidence of a shared ancestry between the Coyotes on Galveston Island and Red Wolves. In their own words, the authors speculate that their findings could reflect…

(1) Surviving ancestral polymorphisms from the shared common ancestor of coyotes and red wolves that have drifted to a high frequency in the captive breeding red wolf population and in a small portion of Gulf Coast coyotes; or (2) coyotes in the Gulf Coast region are a reservoir of red wolf ghost alleles that have persisted into the 21st century.

The research published in the Princeton paper shows that the tested animals are by far and away mostly Coyote. In fact, they ARE Coyotes. As stated earlier, the reservoir of Red Wolf genetic code they possess no more makes the Galveston Island canids Red Wolves than the Gray Wolf and Eastern Wolf genetic code they also possess—revealed in the same study—makes the Galveston Island canids Gray Wolves or Eastern Wolves.

Conclusions

One scientific study does not a new fact make. That’s not the way it works.

To firmly establish the significance of the Princeton findings, additional genetic analysis needs to be conducted to verify that the results are repeatable and consistent within the Galveston Island population. It might also be wise to test other groups of Coyotes from all across the Red Wolf’s historic range to determine just how unique the Galveston Island findings really are. The need to search for the ghost alleles in expanded reference groups is probably also warranted in order to confirm they really are from Red Wolves.

Further, research could be done with the goal of determining how the Red Wolf genetic code expresses itself in the form and function of the Galveston Island canids. Actual measurement of individual animals would need to be taken to determine how significantly they varied from normal Coyotes. Behavioral studies could be conducted to learn if and how their behavior is more Red Wolf-like than Coyote.

The need for additional investigation is even noted in the Princeton study, itself…

Our discovery warrants further genetic surveys of coyote populations in Louisiana and Texas to establish the level and extent to which remnant red wolf alleles are found exclusively in admixed coyotes.

And indeed, it does appear that additional studies are on going on Galveston Island and other areas around the country. Regardless, it is likely to take a very long time to sort out the varied schools of thought concerning wild canid genealogy in North America, especially with regards to the Red Wolf and Coyote. There is still a lot of science that needs to be done. Key to it all is the importance of settling the debate on whether the Red Wolf is actually a distinct species or not.

Maybe there is something really special about the Galveston Islands canids, and maybe there isn’t. Altogether this news seems worthy of only being cautiously excited about. The paper’s findings do appear to be reason enough to warrant further study and investigation, but they certainly do not support the notion that Red Wolves can still be found in Texas.

Many—if not most—of the articles reporting on the Galveston discovery referred to the animals found there generically as “wild canids.” This designation was chosen as a way of avoiding committing to describing them unambiguously as either wolves or Coyotes. I’m not going to be as irresolute here. Red Wolves have not come back from the brink of extinction. The wild canids of Galveston Island—and those found anywhere else in Texas—must be considered to be Coyotes.

The research reported in the Princeton paper should not encourage folks to believe that there is an increased likelihood that they will encounter an exotic wild canid in North Texas. In Texas we have Coyotes. Unfortunately, wolves of all varieties have long been extirpated.

Picture from Wikipedia

The Fate of the Red Wolf

I have learned a lot about the Red Wolves through the process of compiling this article. Most importantly, the effort allowed me to re-familiarize myself with the plight of the Red Wolf, and it helped inform me on just how dire their situation has become.

Red Wolves are one of the rarest mammals in North America and they are in real trouble. For a number of reasons, the early successes of reintroduction efforts staged in North Carolina have largely petered out. There are only a handful of Red Wolves still living in the wild—some reports says as few as 14 individuals—and they face numerous threats. Many experts expect the Red Wolf to be extinct in the wild once again within just a few years.

There are a lot of pressing environmental issues to choose from these days, but the tragic story of the Red Wolf is one that is crying out for advocates. Some concerted public outcry might be all it takes to get the attention of people in positions of authority, focus their attention, and help salvage the effort to save the Red Wolf. If you are in search of an environmental cause to support, please take a closer look at this one.

Further Reading

- Princeton Study: Rediscovery of red wolf ghost alleles in a canid population along the American Gulf Coast

- Press Release: Red wolf DNA found in mysterious Texas canines

- Extinct Red Wolf DNA Discovered in Pack of Galveston Strays

- Mystery Canines of Galveston Island

- A Future for Red Wolves May Be Found on Galveston Island

- Galveston photographer’s discovery led to breakthrough red wolf study

- Substantial red wolf genetic ancestry persists in wild canids of southwestern Louisiana

- Return for America’s Red Wolves

- Red Wolf Species Status Assessment

- Updated Red Wolf Recovery Plan Delayed

- Assessment of coyote-wolf-dog admixture using ancestry-informative diagnostic SNPs

- Whole-genome sequence analysis shows that two endemic species of North American wolf are admixtures of the coyote and gray wolf

- It turns out the United States has just one true species of wolf

- Comment on “Whole-genome sequence analysis shows two endemic species of North American wolf are admixtures of the coyote and gray wolf”

- The Original Status of Wolves in Eastern North America

Find it at Amazon

Good work, Chris.