What an amazing summer it has been! I have been pursuing Wildlife photography for over ten years now, and I am still making new and exciting discoveries. What a wonderful hobby this is!

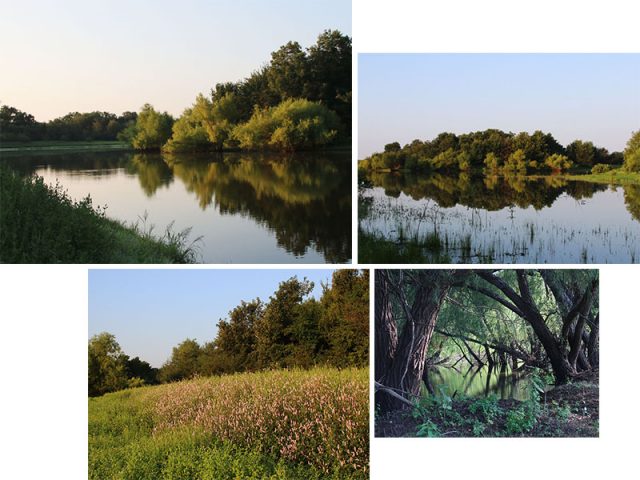

This summer has been special with sights and sounds like few others. The long hard drought of 2012 through 2014 is now just a distant memory. The heavy rains of the past two springs and the resulting flooding has changed the landscape in dramatic way. The dynamic was different out in the field this summer. The deck had been reshuffled.

Let’s take a look at some of the rare, unusual, and interesting wildlife that can be found right here in the heart of the DFW Metroplex—the fourth largest metropolitan area in the United States.

The Month of May

June and July—You’re getting Warmer

Least Terns according to Wikipedia…

The least tern (Sternula antillarum, formerly Sterna antillarum) is a species of tern that breeds in North America and locally in northern South America. It is closely related to, and was formerly often considered conspecific with, the little tern of the Old World. Other close relatives include the yellow-billed tern and Peruvian tern, both from South America.

It is a small tern, 22–24 cm (8.7–9.4 in) long, with a wingspan of 50 cm (20 in), and weighing 39–52 g (1.4–1.8 oz). The upper parts are a fairly uniform pale gray, and the underparts white. The head is white, with a black cap and line through the eye to the base of the bill, and a small white forehead patch above the bill; in winter, the white forehead is more extensive, with a smaller and less sharply defined black cap. The bill is yellow with a small black tip in summer, all blackish in winter. The legs are yellowish. The wings are mostly pale gray, but with conspicuous black markings on their outermost primaries. It flies over water with fast, jerky wingbeats and a distinctive hunchback appearance, with the bill pointing slightly downward.

It is migratory, wintering in Central America, the Caribbean and northern South America. Many spend their whole first year in their wintering area. It has occurred as a vagrant to Europe, with one record in Great Britain.

The least tern arrives at its breeding grounds in late April. The breeding colonies are not dense and may appear along either marine or estuarine shores, or on sandbar islands in large rivers, in areas free from humans or predators. Courtship typically takes place removed from the nesting colony site, usually on an exposed tidal flat or beach. Only after courtship has confirmed mate selection does nesting begin by mid-May and is usually complete by mid-June. Nests are situated on barren to sparsely vegetated places near water, normally on sandy or gravelly substrates. In the southeastern United States, many breeding sites are on white gravel rooftops.[7] In the San Francisco Bay region, breeding typically takes place on abandoned salt flats. Where the surface is hard, this species may use an artificial indentation (such as a deep dried footprint) to form the nest basin.

The nest density may be as low as several per acre, but in San Diego County, densities of 200 nests per acre have been observed. Most commonly the clutch size is two or three, but it is not rare to consist of either one or four eggs. Both female and male incubate the eggs for a period of about three weeks, and both parents tend the semiprecocial young. Young birds can fly at age four weeks. After formation of the new families, groupings of birds may appear at lacustrine settings in proximity to the coast. Late-season nesting may be renests or the result of late arrivals. In any case, the bulk of the population has left the breeding grounds by the end of August.

The really oppressive heat of a normal North Texas summer left us for good in mid-August—the result of a series of truly unusual weather patterns. In its wake was a short pre-autumn season of beautiful and accommodating weather. I love that hint of fall in the air—you feel it when the sunlight is still strong, but the air around you has cooled and is no longer stifling. Its a magical time of the year, and we got it early this season—a kind of reverse indian summer. The result was a season full of wonderful wildlife viewing opportunities. It was as good as it gets!

An August Cool Down

The Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex is rich with surprisingly unique, exotic, and interesting wildlife. In spite of the ever increasing urban sprawl, there has been a counter-intuitive increase in the number and variety of wild animals over the last several decades.

What accounts for this amazing change? There are a number of important factors. Attitudes about urban wildlife are different now. Acceptance and tolerance have replaced “Let’s shoot it” as our first best option. That alone is an important step forward.

Changes in land use have also occurred. Ranches and farms are giving way to suburbia, but in many municipalities, certain parcels are being set aside as parks or allowed to remain wild. This is a magnificant development!

Finally—and possibly most importantly—people in urban areas surround themselves with abundance. Our native wildlife gladly leverages this bounty for its own good. Many urban animals live longer healthier lives and produce larger and more successful litters than do their more rural cousins.

The crosstimbers of urban North Texas call to me like no other place on the map. These forests can be sparse and they can be dirty. They always reflect the close proximity of humanity—there is always sign to be sensed. Discarded or lost trinkets. Trash—bottles and plastic bags. Jet airliners over head or the constant drone of automobiles on the highway. But there is much more to these woods than this.

I don’t know exactly why, but I love the forest and wild places around the metroplex. There are places in this city that are isolated and forgotten. These woods are rarely visited by the presence of people even though they are surrounded by millions. These are the special places—true wildernesses with unbelievably amazing things to be found within. There is a bounty and richness of wildlife in the woods of North Texas that would surprise most. The most exotic wildlife in all of Texas can be found right here in Dallas/Fort Worth!

September Surprises

There is no more appropriate way to end a summer of extraordinary wildlife observations than with a sighting of the extremely rare Swallow-tailed Kite. My good friend, eagle-eyed Phil Plank, made this exciting discovery in Flower Mound, Texas—a place where these kites have never before been documented. A rare bird seen in an unexpected location—it doesn’t get any better than that if you ask me! Nice work, Phil!

A few days later I managed my own shots of this wonderful bird, including this sequence of the kite snatching a dragonfly out of midair. Awesome!

Here’ is how Wikipedia describes the wonderful Swallow-tailed Kite…

The swallow-tailed kite (Elanoides forficatus) is an elanid kite which breeds from the southeastern United States to eastern Peru and northern Argentina. Most North and Central American breeders winter in South America where the species is resident year round. It was formerly named Falco forficatus.

The species is 50 to 68 cm (20 to 27 in) in length, with a wingspan of approximately 1.12–1.36 m (3.7–4.5 ft). Male and female individuals appear similar. The body weight is 310–600 g (11–21 oz). The body is a contrasting deep black and white. The flight feathers, tail, feet, bill are all black. Another characteristic is the elongated, forked tail at 27.5–37 centimetres (10.8–14.6 in), hence the name swallow-tailed. The wings are also relatively elongated, as the wing chord measures 39–45 cm (15–18 in). The tarsus is fairly short for the size of the bird at 3.3 cm (1.3 in).

Young swallow-tailed kites are duller in color than the adults, and the tail is not as deeply forked.

Swallow-tailed kites inhabit mostly woodland and forested wetlands near nesting locations. Nests are built in trees, usually near water. Both male and female participate in building the nest.

Sometimes a high-pitched chirp is emitted, though the birds mostly remain silent.

The swallow-tailed kite feeds on small reptiles, such as snakes and lizards. It may also feed on small amphibians such as frogs; large insects, such as grasshoppers, crickets; small birds and eggs; and small mammals including bats. It has been observed to regularly consume fruit in Central America. It drinks by skimming the surface and collecting water in its beak.

Mating occurs from March to May, with the female laying 2 to 4 eggs. Incubation lasts 28 days, and 36 to 42 days to fledge.

Swallow-tailed kites are not listed as endangered or threatened by the federal government in the United States. They are listed as endangered by the state of South Carolina and as threatened by the state of Texas. They are listed as “rare” by the state of Georgia. Destruction of habitats is chiefly responsible for the decline in numbers. A key conservation area is the Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge in Florida.

So fantastic, Chris! I shared this on the TPWD DFW page too. Hope lots of readers check it out! 🙂

Thanks, Sam! What a summer!

Great photos. Awesome!!! Would love to go exploring with you one day

WOW! I was riveted by every photo. Wonderful! I came down to The Colony from the shoreline of SE Connecticut 10 years ago by myself, and I have missed living, as i did, by a small woods and seeing countless varieties of birds that entranced me. Could you share how to access locations where some of these DFW photos were taken? I very much want to see these avians and mammals for myself; there is so much beauty and wonder out there…. Thank you so much.