We are still dealing with the side effects of last spring’s heavy rain and flooding. Until just recently the spillway at Lewisville Lake has been wide open and the Elm Fork of the Trinity River has been full and flowing faster than it has in years. It’s quite a sight to see. The Trinity in this state is big and powerful. It makes a lasting impression on you when you see it this way.

The bottomlands along the river call out for exploration. You see them everyday on your commute into work. Vista views can be had from the high overpasses of Sam Rayburn Tollway and the President George Bush Turnpike. More intimate looks can be had on State Hightway 121 and Stemmon Freeway. Vast tracks of densely wooded lowlands follow the Trinity River as it winds through the northern Metroplex. Soaring oaks, pecans, and cottonwoods vie for sunlight above a tangled mesh of greenbriar vines and interlocked button bush. Impenetrable in both appearance and in practice. Many of you must have had moments like I have and wondered, just what is in those woods?

Hidden inside this forest is a multitude of small lakes, isolated ponds, and foreboding swamps. These places are especially suitable for urban wildlife. All of this right in the heart of the 4th largest metropolitan area in all of the United States.

Interesting features abound on aerial maps as provided by web sites like Google and Bing. These place can easily become objectives for hikes of exploration. I made several trips into these woods during the months of January and February. On many of these visits I was accompanied by my friend and fellow nature photographer, Phil Plank.

Early one morning, just after we arrived riverside, Phil and I flushed a large bird from the tree we were standing next to. This was a real oops moment—a moment to learn from. The bird was an adult Bald Eagle. We had missed him during our approach, and we milled about beneath him for several minutes without taking notice. Finally the eagle had enough of our intrusion and decided to split. We only managed a fleeting view of the majestic bird as he flew away across the river, disappearing quickly behind the trees on the opposite side. The pictures we took only serve to document the exciting observation.

What happened here is that Phil and I were in the wrong frame of mind while approaching the river. We did not even allow for the possibility of seeing a Bald Eagle, and that was a mistake. If we had begun scanning the trees during our walk up, we likely would have spotted the eagle early and had a much better opportunity to photograph him. As it was, neither of us expected to see an eagle, so it did not even occur to us to look. Simply allowing for the possibility would have made a huge difference here. In fact, that very thing seems to be a key ingredient in so many special wildlife encounters.

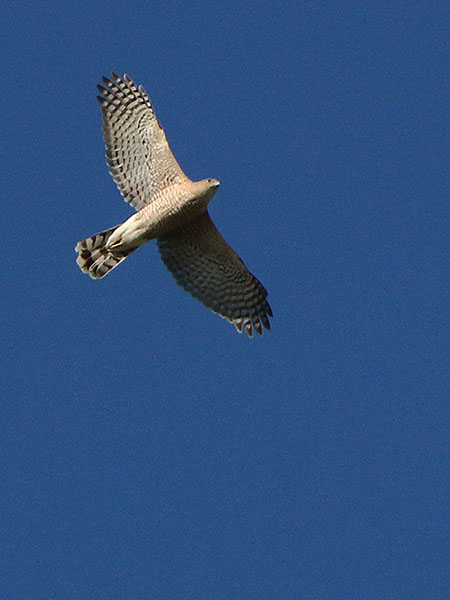

Fortunately, there is another species of big, fish-catching raptor that also shares these haunts. The Osprey—otherwise known as the Fish Eagle—is much more common and often more accommodating than the rare Bald Eagle. Osprey are sleek and beautiful birds of prey, supremely adapted for a life of catching fish. Long curved talons, a sharply hooked beak, long and stall-proof wings, and outstanding eyesight make the Osprey a tremendous hunter.

Most often you will catch a glimpse of an Osprey while the bird is on the wing, soaring through the sky and following the river in search of its next catch. Sometimes you will see one carrying a freshly caught fish in its talons, as the big bird makes it way back to its favorite perch to feed. Osprey carry their prey inline with their bodies in order to streamline their slippery cargo. In this mode the the fish look much like a drop tank on a fighter jet.

Even more rarely, you might actually get to witness the spectacle of an Osprey pulling a fish from the water. I’ve only seen this happen a handful of times. This past winter, Phil and I were granted a front row seat to the show…

From the riverside, Phil and I made our way to the trailhead and entered the forest. In the summer, when vegetation is at its fullest, the woods near the Trinity can be nearly impassable in places. The situation is slightly improved in the winter when the trees shed their leaves and many other plants go dormant.

But, even in our coldest months the flora can be dense in some places. Often evergreen Chinese Privet is the culprit. Considered an invasive species, Chinese Privet out competes many of our native plants. Introduced as and ornamental plant to be used in landscaping, escaped privet thrives in bottomlands like these and will be a difficult genie to put back in the bottle. In the pictures below you can see how the dense underbrush created by these plants can swallow you up only a few steps down the trail.

Exploring the woods along the river is an amazing experience. There is a stark beauty in the leafless forest of a North Texas winter that is good for the soul. A fascinating interweave of bare branches reaches upward creating striking patterns across the crisp, clear azure of January skies. A day in a place like this lifts me up and invigorates me in a way few other things can. Afterwards, I am stronger and more vital for several days onward.

Overall these woods appears static and unchanging, but trees live and die here. Dramatic stories of struggle and growth, triumph and failure can be discerned here if you take just a moment to see the trees revealed from the forest. Ancient oaks brought low by the power of a storm. Young saplings stretching for their place in the sun. Ghostly skeletal silhouettes at sunset. It’s all here in these Trinity River bottoms.

A multitude of marshes, bogs, ponds, and small lakes are also hidden in these woods. Some can only easily be seen using aerials from a tool like Google Maps. These are the places that beg for an in-person visit.

One of the strangest finds I have ever made came as a result of seeking out one these intriguing places on foot. Leaving the trail behind late one afternoon, Phil and I worked our way through the heart of the forest. Our objective was to reach an isolated pond hidden within.

The hike in was mostly uneventful. The tracks of deer and other wildlife abounded, and we used these game trails to our advantage as we made our way.

We were not prepared for what we saw we we arrived at our destination. Instead of a murky swamp of brown or green, we found this sizable pond completely covered in a dense carpet of vivid, blood red. Neither of us had seen anything like it before, and it was stunning to behold. One of the most surreal things I have ever encountered.

A little research back home revealed that the growth on this pond was attributable to an aquatic fern known as Azolla . Here’s is what Wikipedia has to say about the unusual flora:

Azolla (mosquito fern, duckweed fern, fairy moss, water fern) is a genus of seven species of aquatic ferns in the family Salviniaceae. They are extremely reduced in form and specialized, looking nothing like other typical ferns but more resembling duckweed or some mosses.

The plants are typically red, and have very small water repellent leaves. Azolla floats on the surface of water by means of numerous, small, closely overlapping scale-like leaves, with their roots hanging in the water. They form a symbiotic relationship with the cyanobacterium Anabaena azollae, which fixes atmospheric nitrogen, giving the plant access to the essential nutrient. This has led to the plant being dubbed a “super-plant”, as it can readily colonise areas of freshwater, and grow at great speed – doubling its biomass every two to three days. The only known limiting factor on its growth is phosphorus, another essential mineral. An abundance of phosphorus, due for example to eutrophication or chemical runoff, often leads to Azolla blooms.

It still isn’t clear what caused this strange condition, or why it would be localized to this particular pond. According to the sources I referenced, there does not seem to be a reason for concern.

Interestingly, Azolla is not the only thing that can turn water red in the wilds of the Trinity River bottoms. Red Imported Fire Ants respond to a flooding event in an unusual way. When water begins to infiltrate the colony, the ants inside will abandon ship. As the ants leave the mound and enter the water, they cling to each other forming chains and then a clump of writhing little bodies. As the mass grow larger it forms a sort of living life raft for the colony, floating on top of the rolling flood waters.

The vast majority of a colony can collect like this, keeping a good number of its members safe until the flood recedes or they encounter some other way to exit the water.

I first discovered this unique ant behavior as a boy. Suffice it to say that you do not want to bump into floating colony like this one while wading through the water!

The bottomlands of the Trinity River are full of mystery. Strange geographical features like the unusual red pond are just one example. But this is also a rich environment, full of the resources native species need to survive. As you might imagine, wildlife abounds here.

Early morning and late afternoon are the best times to observe wildlife in the Trinity River bottoms. The murky transition between light and dark gives many animals the sense of security they need to feel comfortable conducting their daily routines.

In addition to improving your odds of observing wildlife, an added benefit for the human observer are the absolutely stunning sunsets and sunrises you will be treated to from time to time. North Texas is well known for its dramatic dawns and dusks, the backdrop of the river and its lowland forests only serves to heighten the beauty of these stunning light shows.

Huge flocks of birds—Ring-billed Gulls, vultures, cormorants, herons, and American White Pelicans—can be seen here at dawn and at dusk. In the early morning light, these birds leave their nighttime roosts on and around Lewisville Lake, following the river southward to wherever in the metroplex they spend their days. Then in the evening, just before sunset, they repeat their voyage in the opposite direction. Both events are quite a sight to behold.

The video below includes footage of hundreds of Ring-billed Gulls returning to Lewisville Lake just before nightfall…

On one such morning, having learned my lesson from the Bald Eagle near miss described earlier in this article, I approached the river deliberately and with prudence. Scanning the treeline from a distance I spotted the silhouette of a raptor perched in the very same tree that we had flushed the eagle from just a few weeks earlier.

I used every trick in my book to approach the bird without alarming it. I invested a great deal of time and effort crossing the 300 or so yards that separated us. My hopes were high and I did not want to lose this possible second chance at an up close Trinity River Bald Eagle sighting.

When I finally closed the distance between us by arriving at a well concealed vantage point, I put my big lens on the bird to have a better look at what was what. There staring right back at me was a duly unimpressed and very common Red-tailed Hawk. Fully aware of my presence, the hawk had probably been keeping tabs on me the whole way in. Oh well, the best laid plans…

There is a family group of Coyotes that patrols a portion of these woods and adjoining floodplain. From all indications, four individuals call this place home—one appears to be a little mangy, likely made vulnerable to the disease by eating poisoned rats caught along the margin of nearby businesses and parks.

The territory these Coyotes defend is very important to the group. They make regular rounds and take notice of every intrusion. On most visits Phil and I could count on eventually seeing these prairie wolves. Usually they would be found sitting in a clearing next to a far off treeline, keeping a careful eye on us from a safe distance.

Other times we might get a closer look at the Coyotes if we surprised each other on the trail. This happened a number of times as a result of all six of us going about our business in the stealthiest possible way.

It was very easy to develop an empathy and understanding for the way these animals feel about the land they call home—protective and connected. I imagine it is very akin to the way we feel about our own homes and land.

Visiting the Trinity bottomlands during the day tells only part of the story. To get a more complete picture of the wildlife activity in a certain region, you have to investigate under the cover of darkness. A two week trail camera survey can reveal much about what kind of wildlife these dark forests support. See our results below.

Not far from this spot we found another intriguing location. At this place the trail narrowed as the canopy opened around a swampy section of the forest. Here the path followed a section of dry land that cut the murky body of water.

Also on this section of trail we discovered that some combination of woodland creatures had left a muddy path of their own linking the two bogs. We became curious about what types of animals were making use of this passage, and we set another trail camera here. A week later we had our answers. It turns out this was a very active spot.

On the other end of all of this is McInnish Park in Carrollton, an interesting place in its own right. The high waters of the Trinity have not excluded this park. Flooding has put Carrollton dam under water, and the river has over-banked in some places.

A fascinating variety of wildlife can be found in this park. Even under ordinary conditions McInnish is an excellent location to view certain certain types of urban wildlife. I stopped by briefly one afternoon in late January just to see how things were looking. Here are few of the creatures I observed on that cold winter day…

Great detective work, thanks for sharing !

Another phenomenal entry, Chris! I’ve been telling lots of folks about your blog — these entries are inspirational. 🙂