Dateline – September 19-20, 2015, Lewisville, Texas

In North Texas, there are several different species of herons and egrets—long-necked and elegant wading birds—that come together each year to reproduce in communal nesting sites. Colonies of nesting birds such as these are know as heronies or rookeries, and can consist of hundreds and even thousands of birds. In the Dallas/Fort Worth area these colonies usually form in places consisting of upland woods with a reasonable amount of understory, and a nearby reliable water source, such as a stream or pond.

Prime rookeries locations inspire birds to return to the same place year after year and generation after generation. Great Egrets usually arrive early, beginning in February. They are followed closely by Snowy Egrets, Little Blue Herons, and Black-crowned Night Herons. Cattle Egrets arrive in April and keep the rookery active until well past the end of the summer. Other birds, such as Tri-colored Herons, Anhingas, and more and more often, White Ibises can also be found in North Texas heronies from time to time.

Even in the best of conditions, these rookeries can be brutal places for young birds. Some young birds are even preyed on by other species of herons. Juveniles often fall out of the flimsy nests—pushed out by either assertive siblings or by pure misfortune. Once on the ground, the flightless young birds’ days are numbered. Much death follows and the ground can become littered with the carcasses of the unfortunate ones.

In urban and suburban areas rookeries can sometimes be seen as a nuisance. The large number birds participating in these breeding colonies create situations that are noisy, messy, and smelly. Once a herony is established, the birds and their nests become protected by law. This limits the options available to affected people and businesses, and makes dealing with the resulting problems challenging.

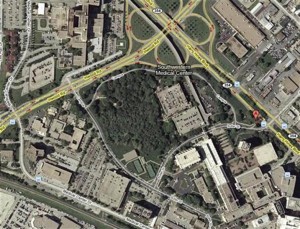

Certain special locations can allow for degree of tolerance. The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Rookery is one such example. This rookery is located in a park-like setting on the campus of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center just a few miles from downtown Dallas.

This is about as urban as a rookery can get. Confined to their wooded area by concrete and buildings, the birds are isolated in a way that helps to prevents them from becoming a nuisance to nearby homes and businesses. The breeding colony has been at this location for decades, and has become something of a minor attraction for the school. In addition to the usual fare, there are some rare and special birds breeding here—Tricolored Herons, White Ibises, and Anhingas are notable examples.

You can read more about this rookery here:

Other recent cases in Carrollton and Allen illustrate some of the problems that can be associated with urban rookeries. In Allen, the city has chased a rookery back and forth between two parks over the last couple of years. In 2014 I visited Stacy Ridge Park to investigate the rookery there. I learned that the previous year the birds had been located in Celebration Park about a mile to the south. Remediation efforts there only succeeded in driving the birds away to Stacy Ridge Park. According to the city of Allen’s web site, efforts to encourage the birds to move on are occurring at both parks this season.

More information can be found here:

The rookery in Carrollton formed along a tree-lined residential street. The situation on Chamberlain Drive was about as bad as an urban herony can get. Bird dropping accumulated on cars, mailboxes, front yards, and sidewalks. The neighborhood was virtually unlivable for most of the summer and into the fall. By law, remediation efforts could not begin until after the birds had left for the winter. Bringing this suburban rookery under control and encouraging the birds to move to a new locations took years of concerted effort and diligence. A unique partnership between the homeowners and the City of Carrollton was require to achieve the desired results without harming the birds.

I did three articles on the situation along Chamberlain Drive. You can find them here:

- Chamberlain Drive Rookery in Carrollton

- Chamberlain Drive Rookery: Death Toll

- Chamberlain Drive Rookery: Victory

Located on College Street near old town Lewisville, the rookery at Wayne Frady Park has the potential to be a colony that can be tolerated. But because of its proximity to residential neighborhoods, an effort will likely need to be made to encourage the birds on to another more suitable location. Some juvenile birds are already beginning to stage in a tree located in the backyard of a nearby residence—certainly not a preferable arrangement. In the meanwhile, the City of Lewisville has been doing an admirable job keeping the droppings and dead birds cleaned up inside the park itself.

Of particular note is the discovery that there are a few White Ibises breeding in this rookery. This once rare bird seems to be expanding its range and is being observed more and more frequently around the Metroplex.

I made two trips to the rookery a Wayne Frady Park. Once in the evening, and a second time early the next morning. Let’s begin with pictures from the first visit:

Wikipedia provides us with some specifics about the different species of birds breeding in the Wayne Grady Park rookery:

Great Egret

The great egret is partially migratory, with northern hemisphere birds moving south from areas with colder winters. It breeds in colonies in trees close to large lakes with reed beds or other extensive wetlands. It builds a bulky stick nest.

The great egret is generally a very successful species with a large and expanding range. In North America, large numbers of great egrets were killed around the end of the 19th century so that their plumes could be used to decorate hats. Numbers have since recovered as a result of conservation measures. Its range has expanded as far north as southern Canada. However, in some parts of the southern United States, its numbers have declined due to habitat loss. Nevertheless, it adapts well to human habitation and can be readily seen near wetlands and bodies of water in urban and suburban areas. In 1953, the great egret in flight was chosen as the symbol of the National Audubon Society, which was formed in part to prevent the killing of birds for their feathers.

Snowy Egrets

The snowy egret (Egretta thula) is a small white heron. It is the American counterpart to the very similar Old World little egret, which has established a foothold in the Bahamas. At one time, the beautiful plumes of the snowy egret were in great demand by market hunters as decorations for women’s hats. This reduced the population of the species to dangerously low levels.[citation needed] Now protected in the United States by law, under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, this bird’s population has rebounded.

Adults are typically 61 cm (24 in) long and weigh 375 g (0.827 lb) They have a slim black bill and long black legs with yellow feet. The area of the upper bill, in front of the eyes, is yellow but turns red during the breeding season, when the adults also gain recurved plumes on the back, making for a “shaggy” effect. The juvenile looks similar to the adult, but the base of the bill is paler, and a green or yellow line runs down the back of the legs.

Cattle Egret

The cattle egret has undergone one of the most rapid and wide reaching natural expansions of any bird species. It was originally native to parts of Southern Spain and Portugal, tropical and subtropical Africa and humid tropical and subtropical Asia. In the end of the 19th century it began expanding its range into southern Africa, first breeding in the Cape Province in 1908. Cattle egrets were first sighted in the Americas on the boundary of Guiana and Suriname in 1877, having apparently flown across the Atlantic Ocean. It was not until the 1930s that the species is thought to have become established in that area.

The species first arrived in North America in 1941 (these early sightings were originally dismissed as escapees), bred in Florida in 1953, and spread rapidly, breeding for the first time in Canada in 1962. It is now commonly seen as far west as California. It was first recorded breeding in Cuba in 1957, in Costa Rica in 1958, and in Mexico in 1963, although it was probably established before that. In Europe, the species had historically declined in Spain and Portugal, but in the latter part of the 20th century it expanded back through the Iberian Peninsula, and then began to colonise other parts of Europe; southern France in 1958, northern France in 1981 and Italy in 1985. Breeding in the United Kingdom was recorded for the first time in 2008 only a year after an influx seen in the previous year. In 2008, cattle egrets were also reported as having moved into Ireland for the first time.

In Australia, the colonisation began in the 1940s, with the species establishing itself in the north and east of the continent. It began to regularly visit New Zealand in the 1960s. Since 1948 the cattle egret has been permanently resident in Israel. Prior to 1948 it was only a winter visitor.

The massive and rapid expansion of the cattle egret’s range is due to its relationship with humans and their domesticated animals. Originally adapted to a commensal relationship with large grazing and browsing animals, it was easily able to switch to domesticated cattle and horses. As the keeping of livestock spread throughout the world, the cattle egret was able to occupy otherwise empty niches. Many populations of cattle egrets are highly migratory and dispersive, and this has helped the species’ range expansion. The species has been seen as a vagrant in various sub-Antarctic islands, including South Georgia, Marion Island, the South Sandwich Islands and the South Orkney Islands.[30] A small flock of eight birds was also seen in Fiji in 2008.

Little Blue Heron

The little blue heron’s breeding habitat is sub-tropical swamps. It nests in colonies, often with other herons, usually on platforms of sticks in trees or shrubs. Three to seven light blue eggs are laid. The little blue heron stalks its prey methodically in shallow water, often running as it does so. It eats fish, frogs, crustaceans, small rodents and insects.

White little blue herons often mingle with snowy egrets. The snowy egret tolerates their presence more than little blue herons in adult plumage. These young birds actually catch more fish when in the presence of the snowy egret and also gain a measure of protection from predators when they mix into flocks of white herons. It is plausible that because of these advantages, they remain white for their first year.

White Ibis

The American white ibis (Eudocimus albus) is a species of bird in the ibis family, Threskiornithidae. It is found from North Carolina via the Gulf Coast of the United States south through most of the coastal New World tropics. This particular ibis is a medium-sized bird with an overall white plumage, bright red-orange down-curved bill and long legs, and black wing tips that are usually only visible in flight. Males are larger and have longer bills than females. The breeding range runs along the Gulf and Atlantic Coast, and the coasts of Mexico and Central America. Outside the breeding period, the range extends further inland in North America and also includes the Caribbean. It is also found along the northwestern South American coastline in Colombia and Venezuela. Populations in central Venezuela overlap and interbreed with the scarlet ibis. The two have been classified by some authorities as a single species.

Their diet consists primarily of small aquatic prey, such as insects and small fishes. Crayfish are its preferred food in most regions, but it can adjust its diet according to the habitat and prey abundance. Its main foraging behavior is probing with its beak at the bottom of shallow water to feel for and capture its prey. It does not see the prey.

I will close this article with pictures and commentary from the my early morning return visit to the park. I’m glad I made the second trip because it revealed things to me that I hadn’t noticed the night before. First there were many more birds present in the morning than were there when I left the night before. Herons must have continued returning to the rookery for another hour or two after I left. In the evening I might have estimated the number of birds in this rookery to be only several hundred, but when I returned the next morning it was clear there were a thousand or more living in this park. Pictures with captions follow:

As always, wonderful entry and photographs, Chris.

Great writeup with pictures. Interesting how they settle down right in the middle of the concrete jungle.