We like to imagine that nature is static and unchanging. It is somehow comforting to believe that our environment and its wild inhabitants do not and should not vary. But the old cliche about change being the only constant applies to the natural world just as it does to almost everything else. To one degree or the other all of nature is in a constant state of flux.

Change in nature can be as simple to observe and explain as a pond drying up after a long hot dry spell. It can also be much more subtle, like the way a wooded area reconfigures itself over time as old trees die off and are replaced with new ones—from the outside looking in the forest appears monolithic and immutable.

The distribution of certain types of wildlife across the countryside can also vary with changing conditions. Animals are quick to exploit new areas that can provides for their needs. They are also forced to abandon those places that are no longer conducive to their long term survival.

These kind of major changes can take eons to transpire, but they can also take place within the lifespan of an average person. I have lived in the DFW Metroplex for over 30 years now, and I have witnessed a few of these shifts myself. There are some animals living among us now that were not here just decades ago, and there are others that have become exceedingly rare, or have even vanished altogether, over that same time period. Let’s take a look at a few examples…

What Was…

The animals listed below are examples of wildlife that I encountered on a regular basis as a young man but seldom or never come across these days. The suggestion that these animals were abundant in the past, but are no longer, is mostly anecdotal. I do not have hard scientific data to back up the assertions I am making here, although many of the changes in distribution and number that I mention are generally recognized by the scientific community.

This list is also not likely comprehensive. I would be very interested in hearing stories that confirm or conflict with those I relate below. I would also be glad to hear about any omissions I might have made.

Northern Bobwhite

When I was a boy the Northern Bobwhite was a fixture in the fields and meadows around our North Texas neighborhood. The “Bob-Bob-White” whistle of the male was heard with regularity. In the field I had the startling experience of flushing a covey of quail at close range on many occasions. On our back roads it was not uncommon to catch a glimpse of a mother quail followed by a disciplined queue of her precocial brood.

The last time I can remember seeing a wild Northern Bobwhite in North Texas was sometime in the early 1980s. The decline in numbers and constriction of the bobwhite’s range is generally acknowledged. Habitat destruction is often cited as the cause. The situation continues to be studied, and I am aware of at least one reintroduction effort that has taken place in the metroplex.

Box Turtle

In North Texas we have historically had two species of box turtle—the Ornate Box Turtle and the Three-toed Box Turtle. Both were very common around the neighborhood where I lived in the 1980s, but sometime around the middle of the decade I stopped coming across them.

I didn’t really notice the change until a read an article about their startling decline some years later. Today Texas Parks and Wildlife is concerned enough to have sponsored a project dedicated to recording information about Box Turtle sightings: Texas Nature Trackers: Box Turtle Survey Project

I can only speculate, but it appears to me that the Box Turtle population in the Metroplex may be rebounding a bit of late. I base this suggestion on an increasing number of sightings—both in person and as reported by my readers—over the last couple of years. Let’s hope so!

Texas Horned Lizard

Texas Horned Lizards have been missing in action for a long time as well, and they are another animal that Texas Parks and Wildlife could use your help tracking: Texas Nature Trackers: Texas Horned Lizard Watch

There are still many sightings of these iconic Texas lizards in the western half of the state, but they are few and far between in the east. The last observation I am aware in the metroplex was reported in 2011 from somewhere inside the Great Trinity Forest.

Black-tailed Jackrabbit

As a boy I used to run into jackrabbits with some regularity on rangeland near my home. By the late 1980s there were even a few pockets of them in far North Dallas trapped by urban development and living on large vacant lots.

In 1996 I observed several individuals feeding on the grounds of Addison Airport—I understand that there may still be a small population on that property even today. In general, though, these lagomorphs are not observed with regularity inside the metroplex any longer. Habitat destruction is the likely reason for the decline in number in our urban and suburban areas.

Fortunately, there are still pockets of jackrabbits living around the outskirts of Dallas/Fort Worth in places with suitable habitat, and there appears to be a healthy population continuing to thrive in the western two-thirds of the state.

Thirteen-lined Ground Squirrel

There were a number of places around my hometown where Thirteen-lined Ground Squirrels could be reliably observed. The lake park soccer fields were one such example. I often noticed these ground squirrels breaking for their burrows when a crowd of young soccer players approached too closely. There was another colony living on a farm on the far side of the interstate, and one more at a nearby cemetery. 1982 is probably the last time I observed one of these critters running wild in the metroplex.

Speckled Kings Snake

Every young person should have the experience of having a captured king snake coiled around your hand, wrist, and arm. These powerful constrictors can really put you in a bind. Its enough to make you wonder just who caught who!

The Speckled King Snake is another animal which as a boy I could find just about anytime I bothered to look. The last time I crossed paths with one of these snakes was the summer of 1980. I still get reports of them from time to time, but from the looks of things they are not nearly as numerous as they once were.

What Is…

You might be excited to hear that the catalog of wildlife species that have migrated into the area is longer that the list of animals that we have lost over this same time period. Again, this list should be considered anecdotal because it has not been backed up by research data. Corrections are welcomed.

White-winged Dove

Fifteen years ago you did not find White-winged doves in the Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex. Now they are quite common. Years ago these doves were most abundant in the Lower Rio Grande Valley where they commonly nested in citrus groves. According to the Texas Parks and Wildlife website the White-wing Dove’s range expansion began in the early 1980’s after a series of unusually cold winters decimated the citrus farms that the dove had been calling home. Many of the groves were never replaced. At the same time human population growth and subsequent development in the area gobbled up even more habitat.

By the late 1990’s I began noticing White-winged Doves in Travis County, in and around the city of Austin. By 2005 or so I was hearing their distinctive call here in the metroplex. White-winged Doves can now be found breeding as far north as Oklahoma, and I have even seen reported sightings up into Kansas.

Eurasian Collared-dove

I first noticed the Eurasian Collared-dove in North Texas around 2005, but they had been here for quite some time before that. The collared-dove is an invasive species that, like its name implies, is native to Europe and Asia. In the 1970’s Eurasian Collared-doves were introduced into the Bahamas. From there they made the leap to Florida, and soon the adaptable birds had colonized large portions of the gulf coast and areas inland. Today the collared-dove occurs over most of United State and Mexico.

Crested Caracara

The Crested Caracara is a bird that has become much more common in the Dallas/Fort Worth area over the last ten years or so. The vast bulk of the caracara’s traditional range is in Central and South America. Most range maps show only a thin sliver reaching up through south central Texas to somewhere near Waco. Today, sightings of the opportunistic Crested Caracara occur regularly all around North Texas and even into Oklahoma and Arkansas.

Bald Eagle

Most people are vaguely aware of the general decline of the Bald Eagle across all of North American through the middle and late 20th century. Dedicated conservation efforts brought the bird back from the brink of extinction, and the population has rebounded nicely. In 2007 the Bald Eagle was officially delisted from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife.

As the population began to grow, migratory Bald Eagles were again seen in the winter skies over Dallas and Fort Worth. More recently, year-round resident eagles have moved into North Texas. Just this year a breeding pair in southeast Dallas County successful fledged their second pair of young eaglets.

House Finch

The House Finch is unmistakable with its cheerful song and crown of bright red feathers. This is a bird I certainly would have noticed as boy—but they were not here then.

Originally these little songbirds were native only to Mexico and the American Southwest. In the 1940s some pet trade finches were released in the Northeast where they survived and quickly increased their distribution. The birds in the southwestern United States also began expanding their range northward and the two populations met up sometime in the late 20th century. The House Finch now occurs all across North America.

Africanized Honey Bee

In the 1970s and early 1980s the threat of the coming “Killer Bee” invasion was frequently cited in the news. Killer Bees became something of a pop culture sensation, and several horror/monster type movies were even made about the coming disaster.

These so-called “Killer Bees” are actually just a hybridization between domesticated European Honey Bees and the more aggressive African Honey Bee. Several swarms of these hybrid bees were accidentally released in Brazil in the 1950s and they have been expanding their range northward ever since. The first swarms reached south Texas around 1990 and they arrived in the Dallas/Fort Worth Area by the end of the decade. They are with us now and have been for many years now.

Africanized Honey Bees and their more docile domestic cousin are virtually identical in appearance. Behavioral differences are the key to telling to two types apart. Africanized Honey Bees often build their hives in places that domesticated bees would not, such as ground cavities.

Africanized Honey Bees don’t roam about the countryside looking for people to sting. Nor are they unusually aggressive when out collecting nectar. They are, however, much more proactive about defending their hive than are European Honey Bees. They are quicker to attack intruders, and continue the defense of their hive much longer and at a greater distance than do domesticated bees. In North Texas, your best best is to just steer clear of any hives you come across. Disturbing bee hives—whether they contain European or Africanized Bees—is just a bad idea.

American Alligator

The American Alligator was threatened with extinction just a few short decades ago, but concerted conservation efforts brought them back. By 1987 the population across the southeast United States had recovered to the point that the American Alligator could be removed from the Endangered Species List.

The Dallas/Fort Worth Area is approaching the northern limits of the American Alligator’s range. Their occurrence in the Metroplex likely varies depending on trending climate conditions. Right now they can be found in many of our lakes, wetlands, and in all branches of the Trinity River.

American Alligators in North Texas are secretive and often frequent hard to reach places. They are stealthy and difficult to observe. All of these factors come together to ensure that human-alligator conflicts are almost unheard of here in DFW.

White-tailed Deer

As a boy I was very interested in the White-tailed Deer. From the late 1970s through the mid 1980s I spent a lot time in the woods around my hometown hoping to see one or to find some sign. I never did.

Some time in the mid 1990’s the situation changed. For some reason deer began moving into the Metroplex from outlying areas. By 1996 I began to notice deer crossing signs installed along highways in certain parts of the city.

Today there are a lot of White-tailed Deer living among us. They can show up in sometimes surprising places. A few deer have even make their way well inside the city limits of Dallas.

Deer are approaching the size limit for big mammals trying to eke out a living in an urbanized environment. Resource acquisition and hiding places become a challenge for animals as large as White-tailed Deer. Somehow here in DFW quite a number of them are finding a way!

Zebra Mussel

The Zebra Mussel is one of the newest invasive species to reach our area. Their arrival is generally considered a negative development and efforts are in place to control their spread.

Zebra mussels cement themselves to underwater structures and cluster together in mass congregations. They are know to clog water pipes, and are vary expensive to remove. It is also thought that Zebra Mussels have an negative impact on several species of native wildlife.

Zebra Mussels are native to Black Sea and Caspian Sea in Eurasia. They have since colonized many areas in Western Europe and North America. It is thought that they first reached America via the Great Lake in the late 1980s, possibly introduced in released ballast water from ocean going ships.

Zebra Mussel were discovered in Lake Texoma in 2009. They have since entered the Trinity River watershed and can be found in Lake Ray Roberts and Lewisville Lake. More information about Zebra Mussels and how to deal with them can be found here: Hello Zebra Mussels. Goodbye Texas Lakes.

Feral Hog

Feral Hog were not a problem in the Texas when I was a boy. Now Texas has the largest population of wild pigs of any state in the Union. Several cities in the Metroplex have had to deal with or are actively dealing with Feral Hog problems right now.

Feral Hogs are the descendants of released domesticated animals, and as such they are an entirely man made environmental issue. Wild pigs have the highest reproductive rate of any large mammal and they are prodigious breeders. They are intelligent and adaptable. As adults, Feral Hogs have no natural predators in the North Texas area.

Most human conflict with these animals comes from their habit of rooting up soil in search of grubs, tubers, and other buried foodstuff. Although of minor consequence in natural areas like the Trinity River bottoms, this rooting behavior can wreak havoc on yards and golf courses.

Feral Hogs are not considered game animals and can be hunted at anytime in Texas (though not inside city limits and not without a hunting license). A huge industry has sprung up in the state around the sport hunting of these animals.

River Otter

The playful and engaging River Otter was long thought to only inhabit the eastern most part of the state. Over the last several years many of these intriguing animals have been observed in the Dallas/Fort Worth Area making their way along the Trinity River and its many tributaries. One of the most compelling sighting I am aware of occurred just this past winter when an adult River Otter was photographed near the White Rock Lake spillway in Dallas, Texas.

Conclusions

The reasons for all of these changes are not always clear. Often flat-out speculation is all there is. Habitat loss or modification due to urban sprawl is frequently noted. As is climate change. The invasive Red Imported Fire Ant is considered a possible cause in the decline of several ground nesting species. It is not hard to imagine vulnerable hatchings falling victims to the aggressive fire ants.

In truth, the real answer is probably comprised of a complicated mix of several different factors. Human activities and attitudes play an important role. As do long term climate trends. The adaptability—or lack thereof—of some animals is another major consideration.

People can reconfigure environments in sometimes drastic ways. Whether this hurts or helps a particular animal all depends upon what the new habitat has to offer. Urban development can be a challenge for native Texas wildlife, but for some animals it can also provide a real bonanza. Where there are people there is abundance. Food, water, and shelter can be more plentiful and reliable in developed areas than they are outside the city. Adaptable wildlife can find ways to exploit this bounty.

The attitudes people have about wildlife make an important difference as well. More and more, people are seeing wildlife as something of value and importance. In places where it is reasonable for humans and animals to coexist, more people seem open to the possibility than they might have been in the past.

Our local city leaders also appear to be increasingly committed to expanding the green spaces inside our townships through the creation of parks, green belts, and nature preserves. When humans and wildlife do come into conflict it is becoming more common for municipalities to address these problems responsibly and with restraint.

Long term climate trends likewise can play a key role. An extended drought, like the one we have been experiencing for a number of years now, can have a major impact on native wildlife. But the exact same conditions that hurt some species can be more accommodating for others. Warmer weather or drier conditions might allow some animals to expand their range by permitting them to breed farther north or by encouraging them to disperse in ways they normally wouldn’t.

The question remains, though, whether these changes are positive or negative. The answer, as is so often the case, depends mostly on your point of view. For animals moving into the DFW Metroplex and exploiting new territories and expanding their range the transition is certainly a positive development. And, of course, the opposite is true for those animals losing ground, for whatever the reason.

For people, new wildlife can offer unique and interesting things to observe and enjoy. But often new or invasive species come with a whole host of difficult to deal with problems. Typically the more successful a species is at adapting to an urban environment, the quicker they become saddled with the label of “pest” by the people they live in close proximity to. The price of losing species to changing conditions is even harder to gauge, especially in an urban habitat where wildlife and its impact on the environment is so easy to overlook.

What Is – UPDATED: September 16, 2022

Mississippi Kite

Much of the evidence for the addition of the Mississippi Kite to this list is anecdotal, but I believe a reasonable case can still be made. Mississippi Kites have long been know to have a distribution that included the Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex, but until the last 10 to 15 years they were rarely reported in the metroplex. Over the last several years things seem to have changed.

I see Mississippi Kites around town much more frequently these days than I did even 5 years ago. I often find them circling over our neighborhood and flying along our greenbelt park, whereas just a few years ago I did not. There is evidence that mated pairs have nested in several different locations around our subdivision and in those adjacent.

The same is true in many other places around Dallas/Fort Worth as well. Further, I regularly receive emails from folks asking about pretty gray falcons that they have never seen in their neighborhoods before. Over the last several years I have come to expect a number of these queries every month over the course of the spring and summer.

The Mississippi Kite is a beautiful bird. I certainly hope that the perception that their numbers are increasing in DFW reflects an actual phenomenon. Keep the sighting reports coming in!

Interior Least Tern

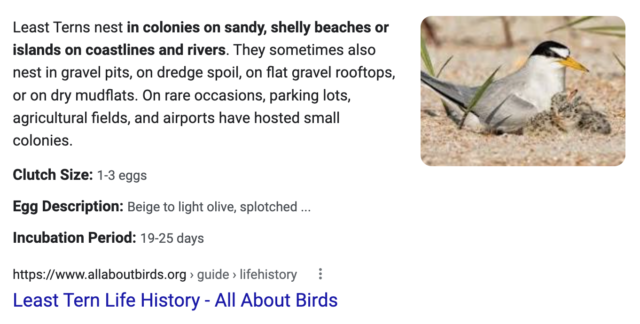

The Least Tern is the smallest and daintiest of all North American Terns. There are three subspecies of Least Terns that are recognized in the United States: The Eastern or Coastal Least Tern, the California Least Tern, and the Interior Least Tern. It’s the latter subspecies that is normally expected in the Dallas/Fort Worth area.

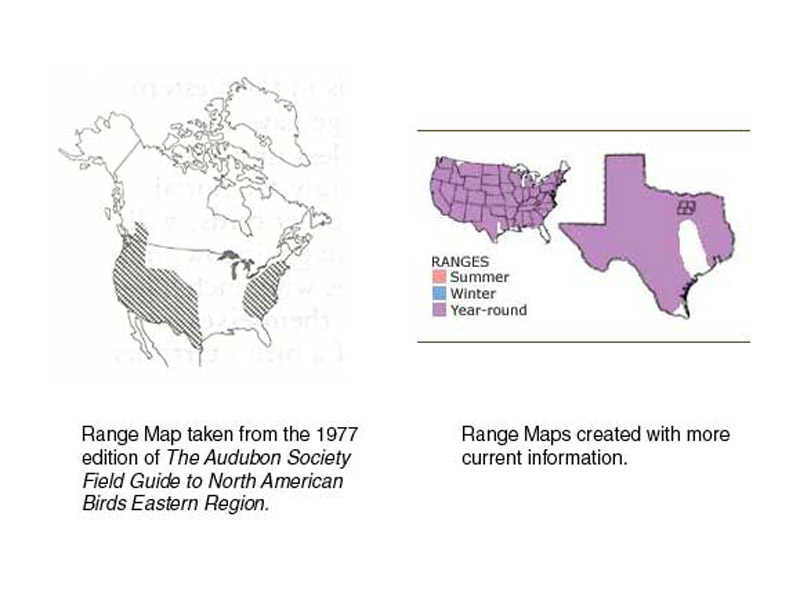

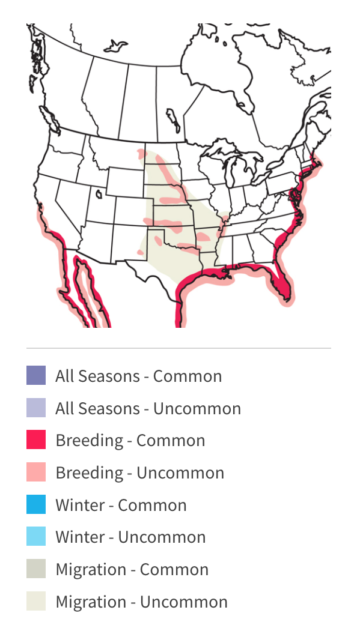

For many years the Interior Least Tern was listed as endangered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. And as you can see on the distribution map to the right, the Least Tern has not typically been considered to range into the DFW metroplex. For much of this time it might seem that migration was largely responsible for Interior Least Tern sightings in our part of Texas.

But things have changed significantly over the course of the last ten years or so. The population of Interior Least Terns has rebounded nicely since they were first listed as endangered in 1985.

At that time there were thought to be less that 2000 individuals left in the wild. The latest estimates reflect a healthy increase in that number, with counts as high as 18,000 wild birds. As a consequence of this excellent news, the US Fish and Wildlife Service removed the Interior Least Tern from list of threatened and endangered wildlife under the Endangered Species Act in January of 2021.

NOSSAMAN – Service Removes Interior Least Tern from Endangered Species List

The Dallas/Fort Worth Area now is home to a thriving population of these sleek white birds. The secret to their success in the metroplex might be something of a surprise. Breeding grounds for Least Interior Terns have typically included a small and select group of rivers in the central United States. These birds have the habit of nesting in colonies on sand and gravel bars near the rivers. The adult terns then hunt for small fish in the shallow waters to provide food for their offspring. But in DFW, the Lest Interior Tern has been able to successfully substitute flat, graveled covered warehouse roofs—which we have in abundance—for the sand bars they would normally nest on. Because of the way our urban planning has been done, many warehouse districts have been constructed near the Trinity River or one of its many tributaries. The combination of the large flat roofs for nesting and the ample hunting provided by the river, its feeder creeks, and its many borrow pit lakes has proven to be a boon for the Interior Least Tern.

The Interior Least Tern is a remarkable addition to the catalog of Dallas/Fort Worth urban wildlife. A watchful observer can expect to find these terns hunting for small fish at almost any suitable body of water in the metroplex. Even more, the successful recovery of this subspecies is a wonderful reminder that development is not always detrimental to wildlife—sometimes it can even work to their advantage. In the case of the Interior Least Tern, the benefit they gained from human activities was incidental, not purposeful. But that doesn’t lessen it positive affect, and knowing about it may help us to better recognize other similar situations in the future. Maybe there are additional and easy accommodations that can be made to help this species—and others—if we just become a little more inclined to notice them.

Great article Chris! I also think it’s worth pointing out that as certain neighborhoods get older, and the trees mature, that a whole new cast of animal characters move in. I first moved to Texas into a newly constructed subdivision in Collin County in the late 1980’s. I used to frequently see animals like raccoons, armadillos, bobwhites, roadrunners, possums, snakes, frogs, turtles, tarantulas, toads and all kinds of birds of prey when I first moved there. We even saw a Prairie chicken in our backyard once. Fox squirrels and cottontail rabbits were pretty much non existent. Then, as the trees matured and the plant cover around the houses grew during the late 1990’s and 2000’s, I began to see way less of the original creatures, and a lot more of the now common rabbits and squirrels. Now I see a different set of animals including coyotes, bobcats, great horned and eastern screech owls, ducks in the pool, and lots and lots of woodpeckers. I think the mature trees provide a much more suitable habitat for some, and the increased numbers of prey items attract the predators in greater numbers. I haven’t seen any of the animals on my first list in years. The last time I saw bobwhites in my neighborhood must have been around 1992. Thanks for sharing your insight into these changes within our ecosystems!

Thanks for the great comment, Matt. You make a excellent point. There are a number of wildlife changes that occur as a neighborhood matures. One example that I remember distinctly from my youth is when Blue Jays and Northern Cardinals began appearing in our yard. The key to their arrival was the maturation of the trees and landscaping around our neighborhood.

-Chris

Good stuff! Great deer photo.