Dateline – October 23, 2021 – Carrollton, Texas

I found this little urban wildlife micro-drama playing out in the alley behind my house. Below is a picture of a very sick rat—likely poisoned with an anti-coagulant marketed as a rodent poison.

One of the effects of rodenticide poisoning is a very intense thirst that encourages the affected rat outdoors in search of water. In this case, the rat had found his way to a small puddle collected in the midline of our alley. This rat was so sick, that all he could do is sit here next to the water and take an occasional drink. He was in such a stupor that he did not respond to anything else—not even cars passing over him on multiple occasions.

While I watched, a Northern Mockingbird came to the same puddle to drink. Before long the bird took notice of the stunned rat and began to harass him a bit. The mockingbird took a particular interest in the rat’s worm-like or snake-like tail. The sick rodent never responded to any of the bird’s interactions.

did not respond to the mockingbird’s harassment

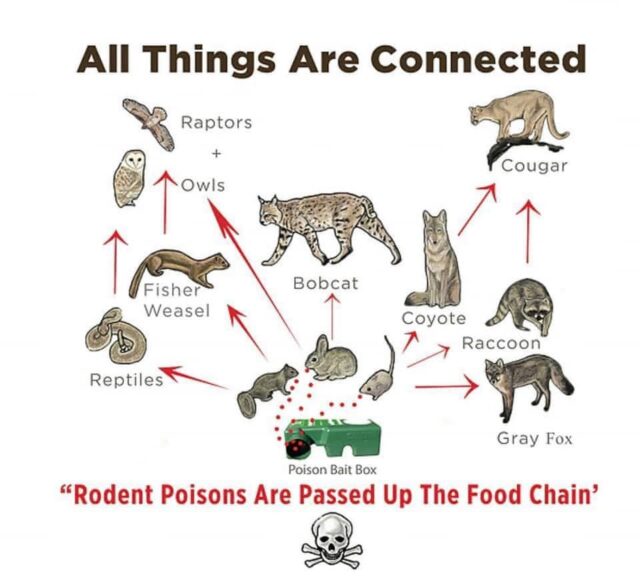

In this weakened state there is a real danger that the poisoned rat will enter the food chain, becoming an easy to catch meal for a cat, dog, Bobcat, Coyote, Raccoon, hawk or owl. The poison in the rat’s system will then be passed on to the predator, negatively impacting the health of that animal as well—possibly even killing it. This is likely counter productive in a sense, as a healthy population of predators in the neighborhood has the potential to be more effective rodent control than the rodenticide.

Eastern Screech Owl.

Photograph from Maryland Zoo

As an example of what is potentially at risk, I present this story about a family of Eastern Screech Owls that lived in my backyard a few years ago. We set up cameras around their nest box in order to keep a close eye on their activities. The full story can be found here.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Accidental Owlets

The nest box that the owls used was a very busy place. In the beginning, the male owl came and went frequently in an effort to keep his mate well fed as she incubated their eggs. Once the eggs hatched he had to redouble his efforts as there were now many more mouths to feed. Eventually, the female was able to join in the hunting effort, and the pair came and went from the nest box like clockwork.

Small reptiles, like Mediterranean Geckos, made up the vast majority of the prey animals brought to the nest. But on rare occasions, one of the owls would return with a rat. Every time this happened, I worried that it was a poisoned rat about to be fed to the growing owlets inside the nest box.

Screech owls are relatively small birds. An adult is only 6 to 10 inches tall—roughly the size of a man’s hand held up with the fingers outstretched. A typical rat can be just as large as one of these owls, and certainly a good deal heavier.

These little owls are capable hunters, but even so, taking on a prey animal as large as a rat would—under ordinary circumstances— present a serious challenge for a bird this small. But a rat that was disabled by rodenticide poisoning would be much easier for a screech owl to subdue.

If a poisoned rat were to be captured and taken back to the nest, it would certainly be fed to the young owlets inside. The rodenticide in the rat’s system would then be passed on to the juvenile birds, negatively impacting their development and possibly even killing them. Fortunately, this outcome never occurred with the owls in my backyard, and the babies grew large enough to leave the nest.

The owls in this story dodged a bullet, that much is certain. But the next family may not be as lucky. The sick rat I found in our alley is evidence that at least one of my neighbors is using rodenticide. If it happened to enter the food chain then other animals might die as well. That’s what’s at stake. The decision to use rat poison should always be weighed carefully.

RELATED ARTICLE: Rat Poison in Prey Threatens Owls, Other Animals