Dateline – October 2021 – Lewisville, Texas

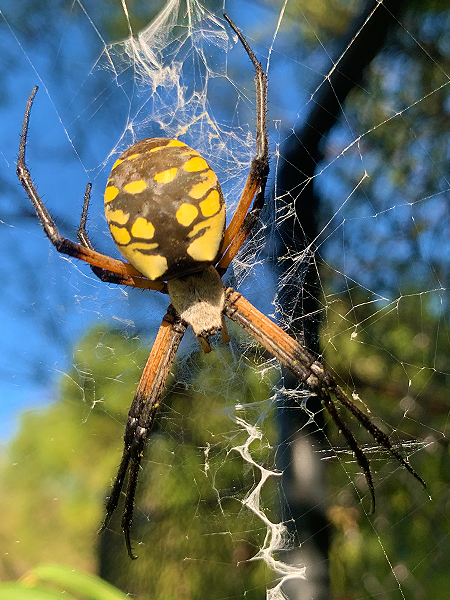

For several weeks, starting in mid August, big Black and Yellow Garden Spiders (Argiope aurantia) become ubiquitous all across the North Texas countryside. The females of this species can grow to be quite large, with body length of around an inch long, and leg-spans approaching three inches. These big spiders construct congruously large wheel-shaped spiral webs, which they use to ensnare flying insects (and other critters).

The intricate webs these spiders build can be several feet in diameter and are typically installed in areas conducive to directing flying insects into the web’s sticky strands. In the case of the spiders addressed in this article, we discovered their webs constructed in various places along the margins between the local dog park and the adjacent woods. The border area between was overgrown with Giant Ragweed, and the big females spiders were fattening up on the bounty of late summer insects found in this lush perimeter of vegetation.

Securing the resources needed for the creation of an egg sack is the name of the game for these spiders. Up to four of these egg sacks can be produced every summer, each time requiring the female spider to invest a great deal of time and energy. Bulking up on a ready supply bugs and insects is how female spiders muster the nutrients required for this sizable task.

on a zig-zag pattern known as the stabilimentum

Any type of insect can be considered fair game for these large spiders. They are even know to feed on small vertebrates such as snakes, lizards, and even the occasional hummingbird. But a staple in late summer and early fall is the plentiful Differential Grasshopper (Melanoplus differentialis). These large yellow grasshoppers become abundant on the Texas landscape as they reach adulthood in late summer, and as such they become a readily available source of much needed protein for hungry Black and Yellow Garden Spiders.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Death of a Hummingbird

Differential Grasshoppers and other large grasshoppers become an evermore important foodstuff as the summer draws to a close. This is true for Garden Spiders and many other types of North Texas wildlife as well. Even animals as large as Coyotes and Raccoons find the nourishment provided by these grasshoppers too hard to pass up. The cooler weather that comes with the approach of autumn makes these grasshoppers sluggish and much easier to catch than would ordinarily be the case. Wildlife in North Texas responds by feasting on the low effort bounty.

RELATED ARTICLE: A Raccoon Feeds on Differential Grasshoppers

If you look closely, you can see three more grasshoppers

in the background.

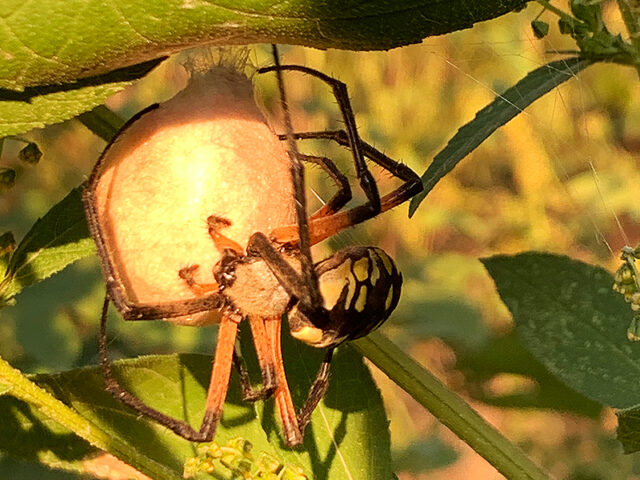

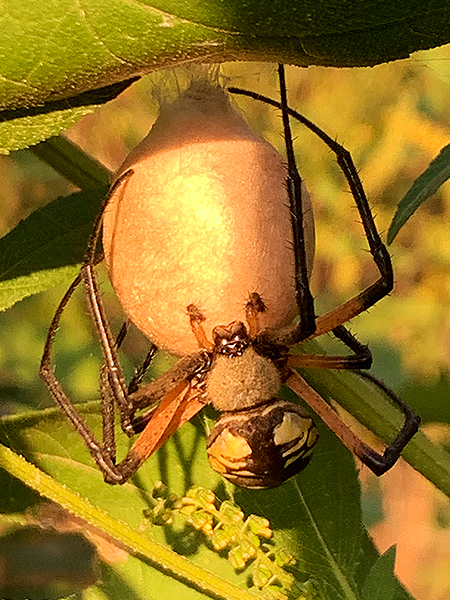

As mentioned earlier, the ultimate goal for the spider is the creation of an egg sack. Up to four can be produced each year. The egg sack of the Black and Yellow Garden Spider is constructed in stages. First, a small pad of webbing is produced by the female spider. She then lays up to a 1000 eggs onto this pad, before bundling it up into a ball. The round egg sack is attached vegetation or some other anchor, and the female begins adding more layers of webbing. Around and around she goes, enlarging the egg sack with each pass. For added protection, the female spider may further enhance the safety of her construction by bending leaves and stems as a canopy over her egg sack. Additional webbing is used to hold these protective fixtures in place.

The eggs inside the sack will actually hatch in just a few weeks, but the baby spiders do not emerge immediately. Instead, they overwinter inside the egg sack, and only seek to exit when the weather warms up in the spring. At that time hundreds of tiny spider will exit the silken construct in a scene similar to those illustrated in the photos below.

Once outside of the egg sack, the baby spiders will find a suitable perch and then release a gossamer strand of webbing. When the length of the thread is sufficient it may be lifted by the wind, carrying the juvenile spider along with it. This unique spider behavior is known as “kiting or ballooning” and is designed to distribute the baby spiders far and wide. With a little luck the wind will transport the baby spider to a suitable and nurturing environment. There, the spider will begin hunting and feeding in order to grown large enough to take on its role in the cycle of life. She will have A LOT of growing to do!

Photograph from DailyMail.com

Photograph from DailyMail.com

Do you have an idea how warm it needs to be before the spiderlings emerge? I am monitoring a couple of egg sacks on my property and would love to see the emergence!