Dateline – July 8, 2021 – Cooke County

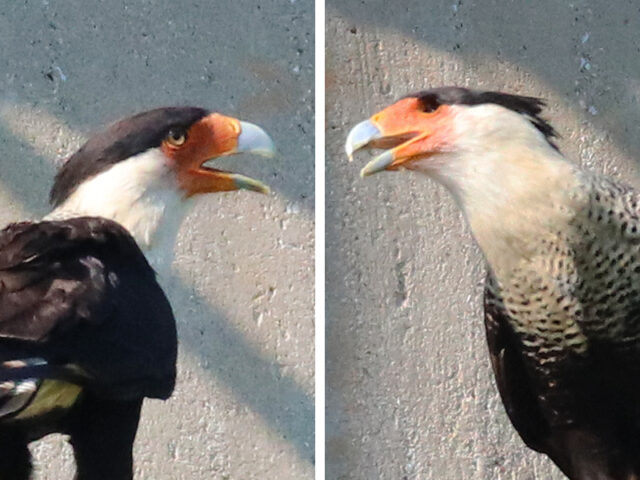

A few weeks ago I received an intriguing email. The correspondence contained pictures and video of a pair of Crested Caracaras perched atop various structures of an abandoned WWII-era army base located in far North Texas.

For those who aren’t familiar, the Crested Caracara is a large, unique looking falcon that is only occasionally seen in our part of North Texas—they are much more common throughout south Texas.

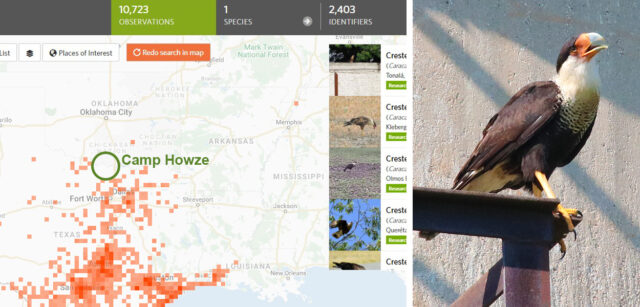

The location of the emailed footage was described as being just shy of the Red River—which in my experience is very far north for this species. A quick visit to iNaturalist.org showed that while it is not altogether unheard of for Caracara to be observed at this latitude (they sometimes even range into Oklahoma), confirmed sightings did appear to be relatively rare.

Moreover, there was a noticeable gap in observations in this particular part of North Texas, which strongly suggested a follow up visit on my part was in order. The mention of ruins of an old army base just sweetened the deal for me. I had not heard about an abandoned base in the area before, and the idea of seeing what was left of the 75 year old military compound really appealed to me.

Cooke County is a little bit outside the normal coverage area of this web site, but between the ruins of an old Army base and the sighting of rare Crested Caracaras, it seemed as if an exception to the typical was more than called for. I would definitely have to make the hour long drive up to Gainesville to have a look for myself!

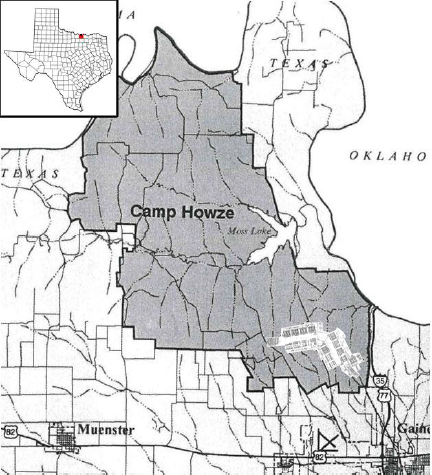

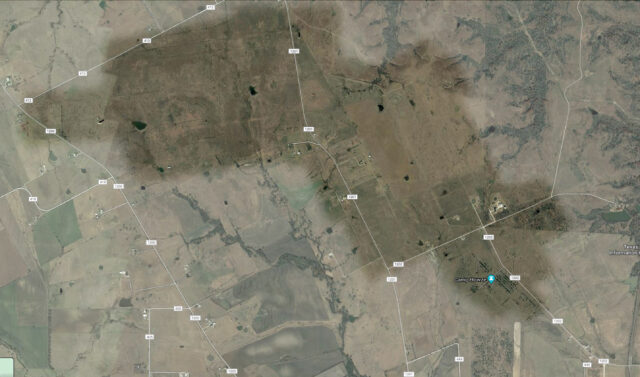

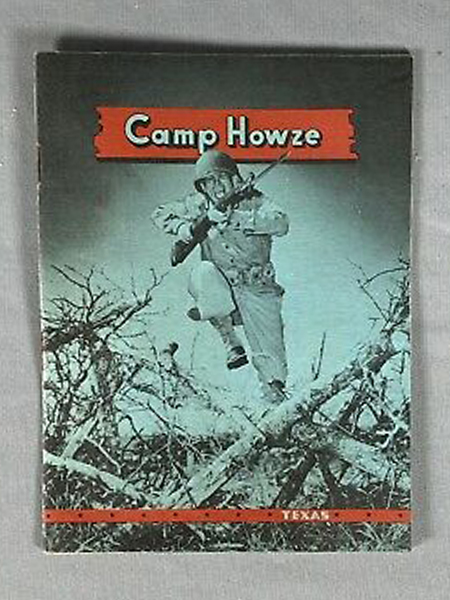

But before I made the trek to Cooke County, I wanted to learn more about the history of the old army compound. I went to Google to pull on that thread a bit, and soon discovered that the abandoned military base had been known as Camp Howze, a sprawling World War II training facility that covered almost 60,000 acres (95 square miles) of North Texas countryside. Camp Howze encompassed large swathes of Cooke County. Its boundaries included the lands just west of Gainesville proper, and then north to the Red River, stopping at the border with Oklahoma.

60,000 acres / 95 square miles

Note the absence of observations around the old military base.

Pictured on the right is a large female Crested Caracara.

Click to Enlarge

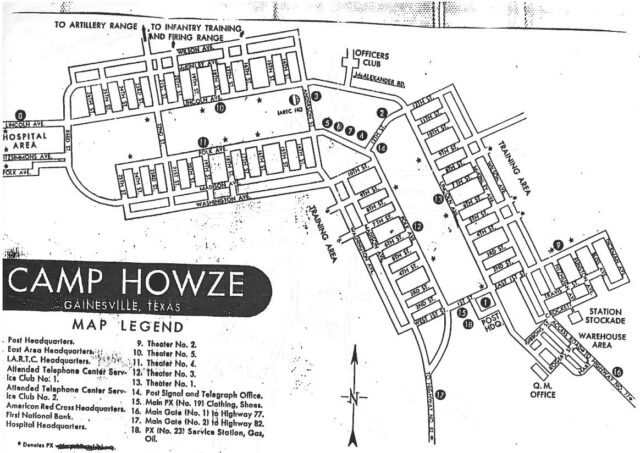

Camp Howze was in operation for four years—from 1942 until it was dismantled in 1946. According to information found on the internet, construction of the camp began early in 1942, just shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The unassuming buildings were completed quickly, and almost over night a virtual new city had sprung up on the rolling plains just west of Gainesville, Texas. The base came complete with rows and rows of barracks, support buildings, an officers club, a hospital, five movie theaters, a motorpool, an artillery range, a mock German village for training purposes, an airfield, and eventually, a POW camp and hospital where around 3000 German prisoners of war were kept.

Click to Enlarge

When the base was at its peak of operation, it had the capacity to handle over 40,000 servicemen. Interestingly, the 1940 federal census showed that Cooke County had a population of around 25,000 people. At the time Camp Howze opened its doors in the summer of 1942, the population of the county more than doubled almost instantly. During its time in operation around 90,000 servicemen received their training at this facility before joining the war effort in Europe.

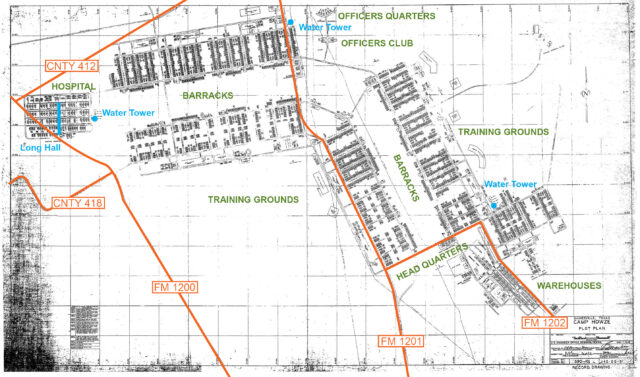

overlaid and annotated with modern roads (orange), notable ruins (blue),

and original base facilities (green)

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge

Road Trip

There are few things I enjoy more than driving cross-country in Texas. I always try to keep my eye out for the unusual when I’m on the road. This time around it was sustainable energy operations that were first to draw my attention as I approached Gainesville. There are large solar farms in a couple of different places in Cooke County. And farther to the west—out near the horizon—there were a great number of wind turbines at work. Below are some articles I found online about the Cooke County operations, offering opinions on the developments in both a positive and negative light…

- Gainesville Daily Register – Construction to Finish Soon at Solar Farm

- Gainesville Daily Register – Solar Farm Sold: Generating Facility Under New Ownership

- Texas Public Policy Foundation – New Wind and Solar Farms are Flooding Rural Texas

- Texas Public Policy Foundation – Fighting to Keep the Lights On: Cooke County

Camp Howze Exit

Exit 501 for FM 1202 is the place to get off I-35 if your destination is Camp Howze. The exit is just north of Gainesville proper, and it is marked by the unique chess piece brickwork pictured to the right.

A historical marker dedicated to Camp Howze is the first thing you will encounter after traversing the FM 1202 overpass. The marker is located on he south side of FM 1202 in a small gravel pull-off. The ruins of the old base begin approximately a mile west of the marker.

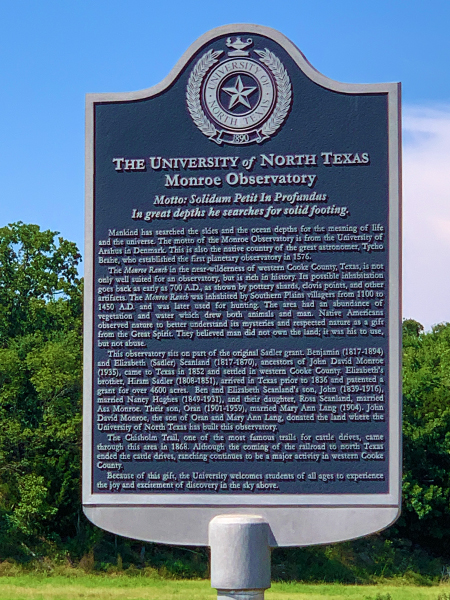

The first thing on the agenda upon arriving in the vicinity of Camp Howze was to quickly get the lay of the land. I made an expeditious circuit of the immediate area in order to help get my bearings. Along the way I traveled as far north as Hubert H. Moss Lake, where I was surprised to find that The University of North Texas keeps a remote astrological observatory. It appears that the dark skies in rural Cooke County offer a quality of seeing that simply is not available anywhere closer to the DFW Metroplex.

UNT’s Monroe Observatory is the primary research site for the school’s astronomy graduate students, and it is equipped with five research-grade telescopes which can be controlled remotely from the university 45 miles to the south in Denton, Texas.

See below for the text

In operation from 1942 to 1946, Camp Howze served as an infantry training facility during World War II. It was named for General Robert Lee Howze (1864-1926), a native Texan whose distinguished career in the United States Army began with his graduation from West Point and included service in France, Puerto Rico, Germany, a South Dakota Indian War and the Philippine Insurrection, 1899-1902. Clifford McMahon of the Gainesville Chamber of Commerce first contacted Federal authorities with the idea of establishing a military installation here. Attracted by the community’s active endorsement of the plan, the government activated Camp Howze on August 17, 1942, under the command of Colonel John P. Wheeler. In addition to infantry training, the base was also the site of a German prisoner of war camp and an air support command base, now part of the Gainesville Municipal Airport. Services provided for the soldiers included camp exchanges, libraries, chapels, theaters, service clubs and a base newspaper, the “Camp Howze Howitzer.” The economic and social impact of Camp Howze on Gainesville was significant and was instrumental in the town’s rapid growth and development. (1982)

There are more wind turbines just barely visible on the horizon

See below for the text

Motto: Solidum Petit in Profundus

In great depths he searches for solid footing.Mankind has searched the skies and the ocean depths for the meaning of life and the universe. The motto of the Monroe Observatory is from the University of Arahus in Denmark. This is also the native country of the great astronomer, Tycho Brahe, who established the first planetary observatory in 1576.

The Monroe Ranch in the near-wilderness of western Cooke County, Texas, is not only well suited for an observatory, but is rich in history. Its possible inhabitation goes back as early as 700 A.D., as shown by pottery shards, clovis points, and other artifacts. The Monroe Ranch was inhabited by Southern Plains villagers from 1100 to 1450 A.D. and was later used for hunting. The area had an abundance of vegetation and water which drew both animals and man. Native Americans observed nature to better understand its mysteries and respected nature as a gift from the Great Spirit. They believed man did not own the land; it was his to use, but not abuse.

This observatory sits on part of the original Sadler grant. Benjamin (1817-1894) and Elizabeth (Sadler) Scanland (1817-1870), ancestors of John David Monroe (1935), came to Texas in 1852 and settled in western Cooke County. Elizabeth’s brother, Hiram Sadler (1808-1851), arrived in Texas prior to 1836 and patented a grant for over 4600 acres. Ben and Elizabeth Scanland’s son, John (1839-1916), married Nancy Hughes (1849-1931), and their daughter, Rosa Scanland, married Asa Monroe. Their son, Oran (1901-1959), married Mary Ann Lang (1904). John David Monroe, the son of Oran and Mary Ann Lang, donated the land where the University of North Texas has built this observatory.

The Chisholm Trail, one of the most famous trails for cattle drives, came through this area in 1868. Although the coming of the railroad to north Texas ended the cattle drives, ranching continues to be a major activity in western Cooke County.

Because of this gift, the University welcomes students of all ages to experience the joy and excitement of discovery in the sky above.

After getting my bearings and seeing what else there was to see, I eventually made my way back to Camp Howze proper in order to have a closer look at what remained. The most readily visible remnants of the old military base were the three large concrete water towers and the numerous still-standing chimney stacks found in various places around the old camp’s plot.

The associated wood-frame build has been long since removed.

I found Black Vultures instead

After the water towers and chimneys, the starkest reminder of the old base’s past were the rows upon rows of large concrete piers used as foundations for the wood frame barracks and other temporary building. I found acres and acres of land still sprouting these structures. Reportedly they have proven very difficult to remove, so the current landowners have just opted to leave them in place. Many of the piers still retain the rusty steel straps that were used to tie-in with the wood frames of the camp’s temporary buildings.

The most intact set of ruins were to be found in the old hospital complex area located in the western most part of the base’s campus. In this part of the facility many smaller, but more permanent, brick structures were constructed. These little building were used as intersections for the long wood framed hallways that connected the various hospital rooms together. A good number of these intersection constructs are still standing.

And what about those Crested Caracara that were the original motivation for this visit? Well, I found them too!

Those two particular birds stayed on the move while I was on site, changing their perches frequently while going about their business. The caracaras appeared and disappeared several times as I made my circuits around the remnants of the old base. After each lap I would have to work to reacquire them. But, the birds seemed to have a particular affinity for certain Camp Howze ruins, and they were spotted perched on those structures time and again as the afternoon progressed.

by the striking black and white patterns formed by the bird’s plumage

particular caracara was missing his left eye. An old injury, no doubt, as the wound

seemed completely healed, and there were no signs the bird was unduly bothered by it.

This kind of size differential is common among raptor species

colored feathers may be a reflection of relative youth

possibly compensating for his missing eye some how

old metal tower—another remnant of the old military base

Crested Caracara are interesting and unique birds. There is some anecdotal evidence that they are becoming more and more common in our part of North Texas. Here is some of what Wikipedia has to say about these large and difficult to categorize falcons…

The crested caracara has a total length of 50–65 cm (20–26 in) and a wingspan of 120–132 cm (47–52 in). Its weight is 0.9–1.6 kg (2.0–3.5 lb), averaging 1,348 g (2.972 lb) in 7 birds from Tierra del Fuego. Individuals from the colder southern part of its range average larger than those from tropical regions (as predicted by Bergmann’s rule) and are the largest type of caracara. In fact, they are the second largest species of falcon in the world by mean body mass, second only to the gyrfalcon. The cap, belly, thighs, most of the wings and tail-tip are dark brownish, the auriculars (feathers surrounding the ear), throat and nape are whitish-buff, and the chest, neck, mantle, back, uppertail-coverts, crissum (the undertail coverts surrounding the cloaca) and basal part of the tail are whitish-buff barred dark brownish. In flight, the outer primaries show a large conspicuous whitish-buff patch (‘window’), as in several other species of caracaras. The legs are yellow and the bare facial skin and cere are deep yellow to reddish-orange. Juveniles resemble adults, but are paler, with streaking on the chest, neck and back, grey legs, and whitish, later pinkish-purple, facial skin and cere.

A bold, opportunistic raptor, the crested caracara is often seen walking around on the ground looking for food. It mainly feeds on carcasses of dead animals, but will steal food from other raptors, raid bird nests, and take live prey if the possibility arises (mostly insects or other small prey, but at least up to the size of a snowy egret). It may also eat fruit. It is dominant over the black and turkey vulture at carcasses. The crested caracara will take live prey that has been flushed by wildfire, cattle, and farming equipment. The opportunistic nature of this species means that the crested caracara seeks out the phenomena associated with its food, e.g. wildfires and circling vultures. It is typically solitary, but several individuals may gather at a large food source (e.g. dumps). Breeding takes place in the Southern Hemisphere spring/summer in the southern part of its range, but timing is less strict in warmer regions. The nest is a large open structure, typically placed on the top of a tree or palm, but sometimes on the ground. The average clutch size is two eggs.

Other Critters

Crested Caracaras were not the only interesting critters that I came across on this sunny July afternoon. One of the funniest encounters I had occurred while I was driving down a lonesome county road.

The street was long, straight and dusty. On either side there were acres and acres of open and lush pasture land—but very few trees. As I made my way along, I soon noticed a pair of nice big trees just down the road and off to the side a bit. These were the only trees producing shade of any consequence for great distances in any direction. Approaching the trees, I could see that the shaded area underneath had become a very popular spot.

On this day, by late afternoon, the temperature had climbed into the upper 90s, and the sheep in the adjacent pasture were looking for a little relief from the heat. Unfortunately for them, the shade from these trees was falling outside the fenced pasture, on the road-side of the barbed-wire.

The sheep were in a quandary, but they had an answer. Several of the more enterprising members of the flock discovered that they could easily push under the fence in certain places, which facilitated a near effortless escape.

So, escape is what they did. Soon the entire flock was outside their enclosure and enjoying the cool shade. I wondered briefly if I should make an effort to notify the owner—whoever that might be.

Instead, I decided that I would drive another loop around Camp Howze, and stop by these trees again as I came back around.

Approximately twenty minutes later I was back, and already the situation was being resolved. The sheep—after having ample time to cool off in the shade—were now headed back UNDER the wire, and back INTO their enclosure. They were doing this of their own accord. They were putting themselves away for the evening.

I shook my head in disbelief and laughed as I pulled away. I would be making a few more laps around the old base before I called it a night, so there would be more opportunities to see how this situation finally played itself out.

On my next spin around I found that ALL of the sheep had now returned to the pasture, and the entire flock was spread out around the enclosure busily munching on the choicest tall, green grass. A happy ending for sure, but this was not going to be my last intriguing discovery of the day.!

My next surprise came as I began to pull away again. This time I noticed a pair of large dark shapes milling about in the drainage ditch next to the road and just a little further down the way. The tall vegetation growing on the roadside made it difficult to be sure what these two animals were at first, but I had my suspicions!

I took my foot off the brake and the car slowly began rolling forward. As I neared the spot, a large Feral Hog emerged from the tall grass and stepped out on to the road. He was soon followed by another. The pair meandered down the street like they owned the place—sniffing here and there as they went. Sometimes they would investigate this side of the road, and sometimes they would poke around on the other. They never seemed much concerned with my presence.

I took a few picture of the pretty pair, and then I was on my way again. It was getting late in the day, and i wanted to try for a few more looks at the caracaras!

At my last stop of the day, while I was standing outside the car waiting for the caracaras to make an appearance, I happened to hear a bird call that I have not heard in the wild in quite some time. This was pretty exciting for me, and I was swept with a wave of nostalgia. It was early in the 1980s—many decades ago—when I last heard this unique bird call in the DFW metroplex. At the time the bird was very common in the Dallas suburb where I grew up, but they have long since disappeared. Evidently, there is still a wild population up Gainesville way. Play the video below with the sound up, and if you can identify the species making the bird call, leave me a message in the comment section below! I bet you know this one!

More Information About Camp Howze

phone directory

In 2014 an Archeologist graduate student from Texas Tech did a fairly comprehensive initial survey of the site as part of his thesis work. His paper is complete with pictures, tables, and measurement of the ruins and artifacts that were discovered. You can read the report he put together here: SCHEIDECKER-THESIS-2014.pdf

For more information about the history of Camp Howze check out the links below…

- Texas Escapes – BLOG – WWII Chronicles: Camp Howze

- Morton Museum – Gainesville, Texas – Camp Howze

- University of Southern Mississippi – 103d Infantry Division WWII Association – Next Stop: Camp Howze

- Gainesville Daily Register – ARTICLE – Powell’s ‘Tales from Camp Howze’ Entertain Crowd

- Wikipedia – Camp Howze, Texas

Bob-white

Bob white!

Thanks for your interesting articles and photos. I enjoy your kind and inquisitive approach to exploring nature!