Dateline – June 20, 2014

NOTE: This post is part of a continuing series of observations: [ First | << Prev | Next >> ]

There was a lot of wildlife activity at the Carrollton park this week, and I have a number of interesting observations to share in this post, but like always I will begin with the Mute Swans.

Our rapidly maturing cygnet continues to do well. He is gaining in size and stature. A nice measure of the young bird’s progress can be found by looking at his feather growth. And, indeed, I made a point of recording the status of the cygnet’s wing and tail feather development in the photographs below.

Moving on from the swans, I again noted an abundance of dragonflies buzzing over and around the water, as is the norm for this time of year. Below are pictures of two of them—a Four-spotted Pennant and a Halloween Pennant.

The Halloween Pennant is particularly striking looking, dressed in orange and black as it is. Here is what Wikipedia has to say this unique dragonfly:

The Halloween Pennant has been described as looking very similar to a butterfly. Its wings are orange-yellow in color, though its markings are dark brown, not black as is commonly believed; the entirely orange-yellow wings with dark brown bands are what has given it its Halloween common name and its typical position of being perched at the tip of a weed stalk, waving in the breeze like a pennant contributes to the remainder of its common name. The young has yellow markings, including a stripe on its back, and adult males develop pale red markings, particularly on the face, though females will occasionally get these red markings too. Halloween Pennants are normally between 38 and 42 mm (approx. 1.5 inches) in size. They feed on other insects, and they are able to fly in rain and strong wind. On hot days, it will often shade its thorax using its wings.

They are commonly found in Central and east North America, particularly in Florida, where they are in season all year round. In the northern part of the range, they are in season from mid-June to mid-August. They can range as far north as south of Canada and as west as New Mexico, but east of the Rocky Mountains. They particularly live around ponds, marshes and lakes, often perched on weedy stems.

Females normally lay their eggs in the morning, in open water, whilst their mate is still attached to them by the head. This method is known as exophytic egg laying. Sexual activity normally occurs between 8 and 10:30 am, and males will normally wait for females to come to them around the edge of ponds, whilst perched on a weed.

A Yellow-crowned Night Heron waited nearby in the dense reed bed. Perhaps he was hoping to nab a dragonfly or two for dinner.

I found the juvenile Scissor-tailed Flycatchers reported in last week’s article quite some distance from their nest. You may remember from my previous post that there were three fledgling scissortails originally. Unfortunately, we lost one of the young birds in the intervening seven days. Fledging is a treacherous time in the lives of juvenile birds. They become too large and active to stay in the nest, and because they are still unable to fly they become very vulnerable, especially if they end up on the ground somehow.

The two remaining scissortail youths were a delight to observe. It is great fun to watch them scan the sky in search of their parents returning with a tasty insect. When the juvenile birds do finally spot their mom or dad it is unmistakable, clearly given away by their rising excitement.

Here is how Wikipedia describes the captivating Scissor-tailed Flycatcher:

The Scissor-tailed Flycatcher (Tyrannus forficatus), also known as the Texas bird-of-paradise and Swallow-tailed Flycatcher, is a long-tailed insectivorous (insect-eating) bird of the genus Tyrannus, whose members are collectively referred to as kingbirds. The kingbirds are a group of large insectivorous birds in the tyrant flycatcher (Tyrannidae) family.

This genus earned its name because several of its species are extremely aggressive on their breeding territories, where they will attack larger birds such as crows, hawks and owls.

Adult birds have pale gray heads and upper parts, light underparts, salmon-pink flanks, and dark gray wings. Their extremely long, forked tails, which are black on top and white on the underside, are characteristic and unmistakable. At maturity, the bird may be up to 14.5 inches (37 cm) in length. Immature birds are duller in color and have shorter tails. A lot of these birds have been reported to be more than 40 cm.

They build a cup nest in isolated trees or shrubs, sometimes using artificial sites such as telephone poles near towns. The male performs a spectacular aerial display during courtship with his long tail forks streaming out behind him. Both parents feed the young. Like other kingbirds, they are very aggressive in defending their nest. Clutches contain three to six eggs.

In the summer, Scissor-tailed flycatchers feed mainly on insects (grasshoppers, robber-flies, and dragonflies), which they may catch by waiting on a perch and then flying out to catch them in flight (hawking). For additional food in the winter they will also eat some berries.

Their breeding habitat is open shrubby country with scattered trees in the south-central states of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas; western portions of Louisiana, Arkansas, and Missouri; far eastern New Mexico; and northeastern Mexico. Reported sightings record occasional stray visitors as far north as southern Canada and as far east as Florida and Georgia. They migrate through Texas and eastern Mexico to their winter non-breeding range, from southern Mexico to Panama. Pre-migratory roosts and flocks flying south may contain as many as 1,000 birds

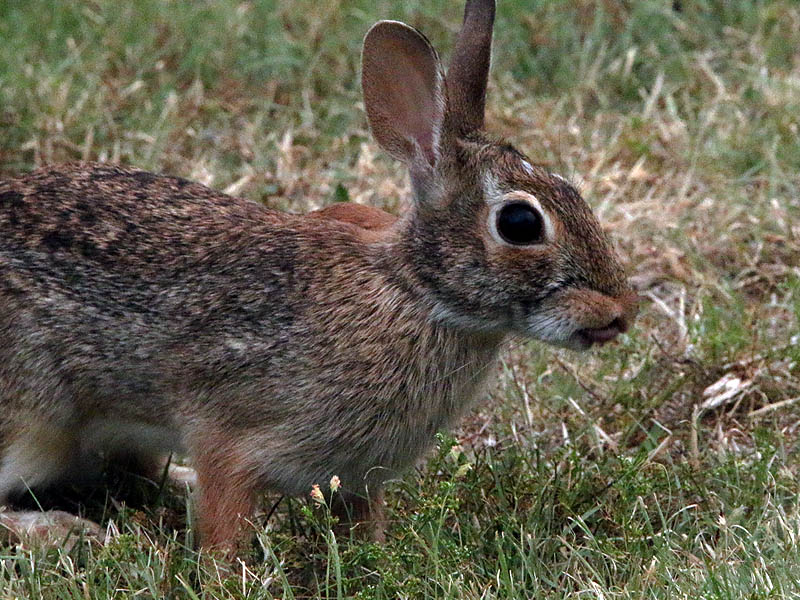

Down by this end of the lake Eastern Cottontails come out of the reeds to feed on the manicured park grass. Many of the rabbits I saw on this afternoon were still very young, at right around two months of age.

There is a small group of House Sparrows that prefer this part of the park as well. I noted a couple of males pass through while I was there, both were in their breeding plumage and one was carrying nesting material.

The House Sparrow is a remarkably adaptable bird, and shows a distinct aptitude for living in close proximity to people. As such, it is a superb example of successful urban wildlife. The House Sparrow originated in the Middle East, but due mostly to deliberate human introductions, has managed to expand its range to most parts of the world. Wikipedia has this to say about the expanding distribution of House Sparrows:

The house sparrow has become highly successful in most parts of the world where it has been introduced. This is mostly due to its early adaptation to living with humans, and its adaptability to a wide range of conditions. Other factors may include its robust immune response, compared to the Eurasian tree sparrow. Where introduced, it can extend its range quickly, sometimes at a rate of over 230 kilometres (140 mi) per year. In many parts of the world it has been characterized as a pest, and poses a threat to native birds. A few introductions have died out or been of limited success, such as those to Greenland and Cape Verde.

The first of many successful introductions to North America occurred when birds from England were released in New York City, in 1852. The house sparrow now occurs from the Northwest Territories to southern Panama, and it is one of the most abundant birds in North America. The house sparrow was first introduced to Australia in 1863 at Melbourne and is common throughout the eastern part of the continent, but has been prevented from establishing itself in Western Australia, where every house sparrow found in the state is killed. House sparrows were introduced in New Zealand in 1859, and from there reached many of the Pacific islands, including Hawaii.

In southern Africa birds of both the European subspecies domesticus and the Indian subspecies indicus were introduced around 1900. Birds of domesticus ancestry are confined to a few towns, while indicus birds have spread rapidly, reaching Tanzania in the 1980s. Despite this success, native relatives such as the Cape sparrow also occur in towns, competing successfully with it. In South America, it was first introduced near Buenos Aires around 1870, and quickly became common in most of the southern part of the continent. It now occurs almost continuously from Tierra del Fuego to the fringes of Amazonia, with isolated populations as far north as coastal Venezuela

Another interesting find at this end of the park was the oddly located spider web in the photograph below. The large web had been constructed in the corner of the boardwalk less than a foot above the surface of the water. Somehow the spider managed to build this web in a near horizontal position. This placement was somewhat of a surprise to me, because I thought that spiders needed the assistance of gravity to layout the framework of their webs. Clearly gravity would have been working against the spider in this precarious location!

Breeding season is almost over for the pond’s resident Mallards, and many of the males are beginning to show signs of their eclipse molt. Most of the juvenile ducks born here are at least semi-independent now, but a number of baby Mallards hatched recently, and a dozen or so week old ducklings can still be found gracing the park. My guess is that these babies represent the last brood of the season. We shall see!

The fledgling Green Heron trio that I reported on for the first time last week have moved from their more secluded birthplace into the main body of the lake. There they have found the marshy north end to their liking. These three young birds do not appear to be receiving parental assistance any longer, but seem fully capable of looking out for themselves now. I observed all three of the young herons for nearly and hour as they stalked in and out of the cattails hunting insects and other aquatic invertebrates.

At one point, the Green Herons each went their separate ways, which opened up an unoccupied stretch of reeds at the water’s edge. A lone American Coot emerged from the depths of the vegetation to briefly fill the void.

The Nutria at this park are very used to the presence of people and are therefore very bold when foraging. Three, four, or more of the big rodents can often be found grazing the green grass bordering the busy walking trail. Some people do not like these large rat-like looking animals, but I find them quite intriguing. I took a few minutes on this visit to video some of their antics. You can find that recording below.

The marshy reed bed at the north end of the lake is packed to overflowing with Great-tailed Grackle fledglings. The park has produced a bumper crop of baby grackles this year and the juveniles and their mothers have moved into the cattails for some added concealment and safety.

But, as you will see in the pictures and video that follow, the added security of the reeds is not always enough when there is a sharp eyed predator on the prowl. The observation below was a particularly gratifying one, because of the good fortune that was required to make it.

As the day drew to a close, an overcast set in muting the favorable lighting conditions and effectively ending my photography session for the afternoon. I was headed back to the car when I registered a slightly unusual but familiar sound coming from a wooded area on the far side of the lake. I listened carefully, but it was hard to hear anything over the drone of nearby automobile traffic. Then there were the sirens of passing emergency vehicles. And then a jet flew by overhead.

A lull in the background noise allowed me to finally hear the sound clearly. I recognized it as the stress call of a harassed Cooper’s Hawk. It was punctuated periodically by the aggressive noise made by Northern Mockingbirds on the attack. I suspected right away that the hawk probably had a recent kill and was trying to feed while dealing with the distraction of mobbing mockingbirds. I rushed over to the far side of the pond, where I had no trouble locating the ruckus.

The Cooper’s Hawk was on the ground in a grassy area under a collection of Mesquite trees. The sleek-looking predator was busy plucking feathers, while three or four mockingbirds dive bombed him over and over again in an effort to drive him away.

On a couple of occasions the hawk did pick up his prey and move a short distance to escape the mobbing birds. First he flew up into a tree. Then to another tree, and then back to the ground. Eventually, the hawk had enough of the harassment and fled for good. He trailed a pair of the relentless and angry mockingbirds as he flew out of sight.

NOTE: This post is part of a continuing series of observations: [ First | << Prev | Next >> ]

Thanks Chris. I always enjoy your journal post. Sharing link on my FB page.

Thanks for stopping by, Mike!