Dateline – May 9, 2014

NOTE: This post is part of a continuing series of observations: [ First | << Prev | Next >> ]

The swan family was on the far side of the pond when I arrived this week. They were feeding on aquatic vegetation in the shallow water near the bank.

On several occasions I observed the swans engaging in “dabbling” behavior similar to that of Mallards and many other ducks. Dabbling is the upending of a bird’s body so that the tail points straight up out of the water and the bird’s head is directed downward toward the pond bottom. This position allows the swans to feed on underwater vegetation that otherwise would be out of reach.

After a time, the family group began to patrol the middle of the lake together. The two young swans are growing rapidly and are just a little over four weeks old now. At this age the cygnets are very nearly the same size as adult Mallards.

Following a quick circuit of the pond, the entire group moved back into the shallow water near the bank and began to feed. The juveniles were a delight to watch as they mimicked the behavior of the adults. Soon all of the swans were covered in dark green strands of algae.

Having eaten their fill, the entire family group left the water and made their way up onto the grassy lawn. For the adults, drying their wings was the first order of business. Immediately upon exiting the water both Mute Swans stretched out their wings and gave them a good, thorough flapping.

The male paused briefly to scratch his bill, and then the group moved up the bank to their preferred spot where the adults and juveniles alike began to primp and preen.

Next was nap time, and all four of the swans were soon dozing in the warm sun of early May.

In addition to the swans there is always a lot of other urban wildlife activity at this Carrollton pond, and today was no different. Spring has definitely sprung in North Texas and there was an abundance of baby animals to be found at the lake. We very nearly approached cuteness overload as you will soon see…

Baby Eastern Cottontails were first on the list. These little fellas were tiny enough to fit in the palm of your hand. Even at this small size, these young rabbits are completely independent and receive no parental care. If you find a small cottontail and it is moving about freely, have no fear. It has not been orphaned, it has just reached that age were it must begin to fend for itself.

Although not nearly as cute as baby rabbit, Great-tailed Grackles were also busy around the pond this afternoon. These abrasive birds have a general unpleasantness about their character—they just look shifty and sinister. In spite of this, I find these birds appealing largely because of their great success adapting to urban living. I don’t know what set of traits make these birds so good at living around people, but it is hard not to root for these avian underdogs.

I have heard it said that Great-tailed Grackles are like rats with wings… but what about real rats? The next animal I came across at the lake was a Hispid Cotton Rat. This little guys was scurrying about, pausing only briefly to feed on grass seeds. His home was in some nearby landscaping, which contained a network of small, tunnel-like trails weaving through the feathery vegetation.

Wikipedia has this to say about the Hispid Cotton Rat:

Hispid cotton rats occupy a wide variety of habitats within their range but are not randomly distributed among microhabitats. They are strongly associated with grassy patches that have some shrub overstory and they have little or no affinity for dicot-dominated patches. Habitat use and preference by hispid cotton rats usually appears to depend on the density of monocots. However, some studies are equivocal on the importance of other vegetation. For example, hispid cotton rats may respond favorably to a high percentage of dicots in a stand if cover remains optimal. In Kansas, hispid cotton rats increased on root-plowed prairie that experienced an increase in the diversity and biomass of early-successional forbs.

Male hispid cotton rats exhibit a lower degree of habitat selectivity than females. In Texas males were found on different habitat types (grassy, shrubby, and mixed) approximately in proportion to availability; female hispid cotton rats tended to choose mixed habitats more often than expected based on availability. Habitat use varies with season and breeding status. In Texas grassy areas with some shrubs were preferred in spring and areas with more shrubby cover were preferred in fall.

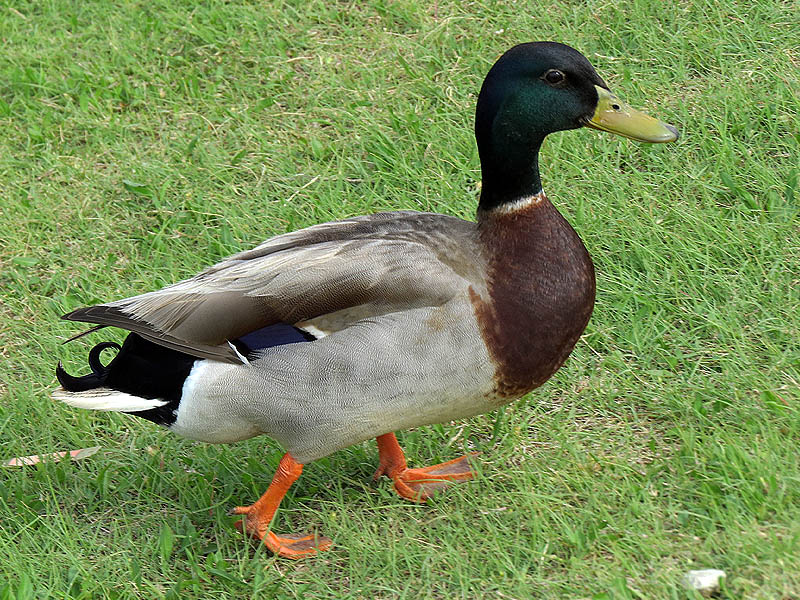

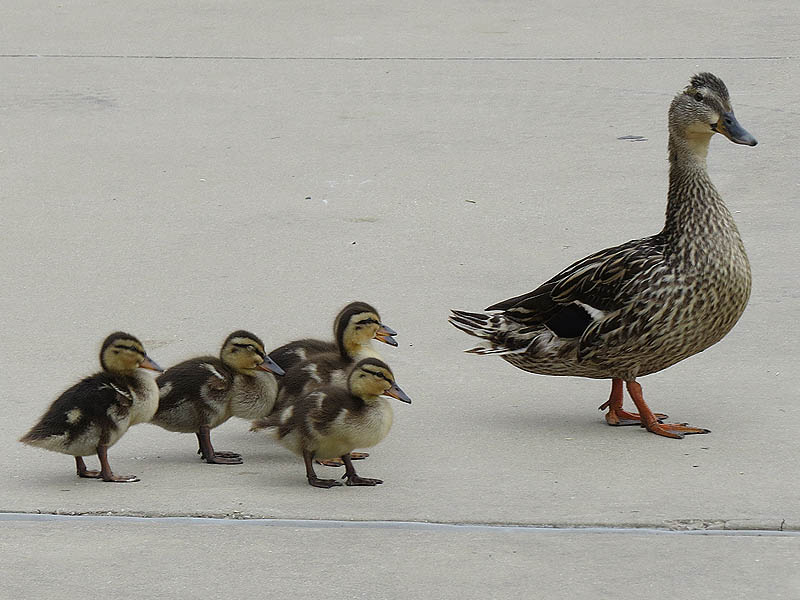

Next came a near endless parade of Mallard ducklings. There were babies of all ages and all were sticking very close to their parents.

Mallard have large broods of up to a dozen or more ducklings. Reproductive rates at this level usually indicate that the mortality rate for the young animals is very high, and that is indeed the case for Mallards. As each week goes by it is striking how the broods get thinned out. Baby Mallards are quite vulnerable to predation, despite the best efforts of their very attentive parents.

Mourning Doves were present at the lake in large numbers on this afternoon as well. These charming birds were combing the ground for seeds, and finding plenty.

Nearby was the Mourning Dove’s close cousin, the Rock Dove or common feral pigeon. This individual was seated on the ground mixing in with a group of male Mallards.

Nutria are an invasive species and are considered a pest by many people. These large rodents superficially resemble Beavers when they are swimming in the water, but once they emerge and expose their long scaly tail, most folks see them in a slightly different light. The River Rat is a common nickname for these animals, which do indeed resemble large. cat-sized rats to a certain degree.

I, of course, enjoy having a chance to observe these creatures and like watching their antics. There are a number of Nutria living in this small lake and almost all are very accustomed to the presence of people. This makes them imminently observable!

Here is what Wikipedia says about the Nutria, which is also sometimes known as the Coypu:

Local extinction in their native range due to overharvesting led to the development of coypu fur farms in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The first farms were in Argentina and then later in Europe, North America, and Asia. These farms have generally not been successful long-term investments, and farmed coypu often are released or escape as operations become unprofitable.

As demand for coypu fur declined, coypu have since become pests in many areas, destroying aquatic vegetation, marshes, and irrigation systems, and chewing through human-made items, such as tires and wooden house panelling in Louisiana, eroding river banks, and displacing native animals. Coypus were introduced to the Louisiana ecosystem in the 1930s, when they escaped from fur farms that had imported them from South America. Damage in Louisiana has been sufficiently severe since the 1950’s to warrant legislative attention; in 1958, the first bounty was placed on nutria, though this effort was not funded. By the early 2000’s, the Coastwide Nutria Control Program (CNCP) was established, which began paying bounties for nutria killed in 2002.[24]:19–20 In the Chesapeake Bay region in Maryland, where they were introduced in the 1940s, coypus are believed to have destroyed 7,000 to 8,000 acres (2,800 to 3,200 ha) of marshland in the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge. In response, by 2003, a multimillion dollar eradication program was underway

Nutria were not the only animals basking on the banks of this small lake. In the picture below you will find a Pallid Spiny Softshell Turtle. This individual’s shell is approximately seven inches in length. Earlier in the season I spotted several that were much larger than this. A couple were likely a foot or more in diameter.

I’ve written about the two ducks below in a previous post: Mallard – Odd Couple. This is a domestic American Pekin Duck with a male wild Mallard, and the pair is inseparable. I have been visiting this park for roughly six weeks in a row, and these two friends are always side by side.

This pond is full of turtles. in addition to the Pallid Spiny Softshell Turtle mentioned earlier, the lake also contains an abundance of the very common Red-eared Slider. These guys can frequently be seen with just their snouts poking out above the surface of the water.

Overwintering ducks love this small lake, and during our colder months there is a wide variety of species that can be found here. By this late in the spring, however, most have left for more northern climes.

A couple of winter ducks are still present though, and the Redhead in the photographs below is an example of such. It’s not clear why this duck has decided to stay in Texas rather than migrate with others of its kind. For some reason he did not feel fit to make the journey, and that may be enough to call his health into question. Let’s hope not!

The Ruddy Duck is another bird that should have migrated away by this time of the year. When I first started visiting this lake in late March there were a dozen or more Ruddy Ducks present. On my last visit there was only this one.

Here is how Wikipedia describes the Ruddy Duck:

Adult males have a rust-red body, a blue bill, and a white face with a black cap. Adult females have a grey-brown body with a greyish face with a darker bill, cap and a cheek stripe. The southern subspecies ferruginea is occasionally considered a distinct species. It is separable by its all-black face and larger size. The subspecies andina has a varying amount of black coloration on its white face; it may in fact be nothing more than a hybrid population between the North American and the Andean Ruddy Duck. As the Colombian population is becoming scarce, it is necessary to clarify its taxonomic status, because it would be relevant for conservation purposes.

On the way out I came across this exotic-looking Yellow-crowned Night Heron. I don’t see these birds very often, but when I do they seem to be generally tolerant of observation. This one was no exception, and I got to have a nice long look at him as he hunted in the cattail reeds.

NOTE: This post is part of a continuing series of observations: [ First | << Prev | Next >> ]

Chris, beautiful series of photographs and a nice description of the animals and their behaviors. You are quite good at finding and documenting these animals. I was particularly impressed that you were able to observe a cotton rat. In all my outdoor tramping, I have only seen their signs, in the form of trails in dense, tall grass, and animals captured in traps for research. Never have I seen a free ranging, untrapped cotton rat.

You mentioned the adaptation of the two exotics, Nutria and Great Tailed Grackle, to their non-native homes, and the control efforts (ineffective) for nutria. I wonder if you are aware that the Eurasian Mute Swan is considered invasive and pestiferous in much of the U.S. Michigan has recently instituted an intensive control program, and the wildlife agency there has said that it intends to eliminate the Mute Swan from the state. It seems that it is quite aggressive and that it is a strong competitor to the native Trumpeter Swan, which had been making a comeback from being extirpated from most of its former range. The Mute Swan is evidently a major factor slowing and in some places reversing this conservation success.

So far I have heard of no ill effects from the few feral Mute Swans in Texas and Oklahoma.

Thank you, David. I am vaguely aware of the Mute Swan’s nonnative status. Invasive or no, I really enjoy watching these animals figure out how to survive in challenging environments. Its one of the things I like best about this hobby of mine.