DATELINE – March 16, 2020

I have been fascinated with Praying Mantises ever since I was a little kid. Mantises are unique and powerful bugs, with head-tilt cool to boot. These mighty hunters are like the cats of the insect world. They are highly accomplished predators, and as such need to have special abilities not found in many other insects. When you watch a praying mantis they seem more engaged than your typical insect. The wheels seem to be turning in their heads as if they are contemplating and figuring things out.

One day as a young boy I tuned into a PBS nature program that just happened to be about the Praying Mantis. Previously I had learned a little about Praying Mantises from books, but this show was my first real exposure to the breadth of behaviors these special insects engage in. I recall the show spending a great deal of time focusing on the hunting techniques of the mantis. The program emphasized the speed at which a praying mantis is able to secure its prey. The narrator urged us to note the way a mantis uses swaying to get closer to its intended victims by mimicking a stem moving in the wind.

Once a praying mantis has spotted his prey, he will use this swaying technique to move ever closer—patiently creeping forward millimeter by millimeter until its unsuspecting victim is within reach. Then like a lightning bolt, the praying mantis strikes out with its two specialized front legs and grabs the prey insect; dragging it back to the mantis’s waiting jaws where the ensnared bug will be quickly dispatched.

The PBS show featured slow-motion footage of mantises capturing House Flies using this technique. Even at this young age I was in awe of how impossibly fast House Flies react, so I was doubly impressed by the mantis’s ability to capture one with ease.

upon elements of the habitat they matured in

In those days I had no idea if we actually had Praying Mantises in North Texas. I was not hopeful that there would be any around our house, but inspired by the PBS program I decided to go out into the yard and see what I could find.

Sure enough, just a short time later I spotted a lanky green Praying Mantis in the landscaping growing along the side of our house. Moreover, this mantis was in full predator mode and actively engaged in stalking a Skipper Butterfly. As I watched, every behavior I had just learned about on the TV show played out in front of me. The mantis slowly inched closer until he was in range of the butterfly, and then he struck out in a flash and nabbed the hapless insect. This was the first time I had ever seen a Praying Mantis in person, and it was the first and only time I have ever witnessed one hunt.

The Carolina Mantis is our native North Texas variety, and they can be quite common in certain places around of Dallas/Fort Worth. We have a large number of them that frequent our local dog park in the summer. It was there that I had another Praying Mantis first when I stumbled across a big green female depositing her eggs on a low tree branch in the early fall of last year.

Praying Mantises females lay their eggs inside a soft, foamy mass. Over time the foam hardens to form a protective shell around the dozens of mantis eggs inside. These egg cases are known as oothecae, and are typically about an inch long, give or take. My expectation was that this particular ootheca would hatch sometime early the in the spring, and I made a vow to keep an eye on it through the coming autumn and winter.

Fast forward into early winter, and I was out for a walk in our neighborhood when I came across a pile of hedge trimming left out on the curb for trash pickup. It occurred to me that I should check the branches for oothecae, and sure enough, I found several mixed in with the cut branches. I broke off a few of the stems with egg cases and took them home with me.

Back at the house, I placed the oothecae I had collected in a container and set it on the shelf for the long, multi-month wait until they would be ready to hatch. I didn’t know much about oothecae at the time (really I still don’t), and as a consequence I was unsure about whether the egg cases I had collected were likely to hatch or not. It was even possible that these oothecae had already produced their brood, but I wasn’t sure how to verify. The only thing to do was to wait to see what happened in the spring.

When March rolled around, I began checking on the oothecae on a daily basis. It was mid-month before something happened—and it was not what I expected! Instead of dozens of nymph mantises, I found the enclosure teaming with tiny, ant-sized wasps!

What had happened!?! I had no idea!

So, off to Google I went to try to find some answers. Maybe not surprisingly, there were not many. Pretty much the only thing I could find that shed any light was this blog article on the Ask an Entomologist website: Do Mantids Get Parasites?

Among several other Praying Mantis parasites—including horrible worms and fungi—this article describes a couple of parasitic wasps that target mantises. The first one mentioned is a Scelionid wasp from the genus Mantidophaga. The adult Mantidophaga wasp lives out its life on a host Praying Mantis. Then, when a female mantis lays her eggs, the Mantidophaga will places its eggs directly into the foamy ootheca as it is being deposited. The resulting wasp larvae will feed on the unhatched Praying Mantis eggs, until the wasp larvae are ready to pupate.

The second type of parasitic wasp mentioned in this article was from the family Torymidae in the genus Podagrion. The lifecycle of the Podagrion is a little different that that of the Mantidophaga. The adult Podagrion does not live on a Praying Mantis host waiting to deposit its eggs in a fresh ootheca, but Instead the female Podagrion seeks out already produced ootheca, and then lays her eggs inside it by penetrating its hard shell with her specialized ovipositor. Just like as with the Mantidophaga, the Podagrion eggs will hatch, and the wasp larvae will feed on the Praying Mantis eggs inside the shared ootheca.

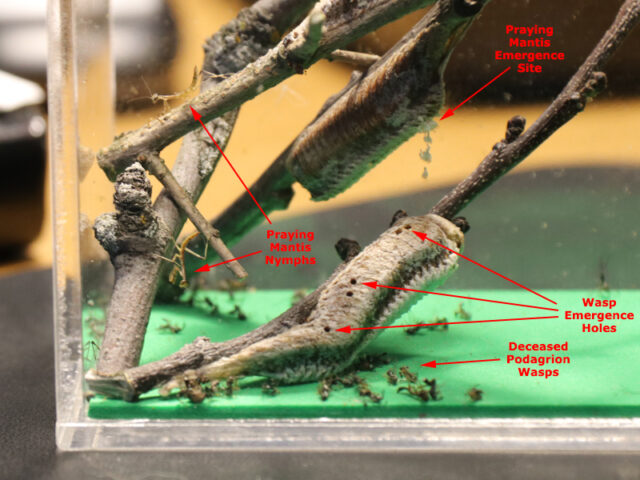

By mid-March the now adult wasps are ready to emerge, and that’s exactly what happened in my case—by the dozens. Upon closer examination it appeared likely that it was Podagrion wasps that had infected the oothecae I had collected. See the pictures below…

This wasp is roughly the size of a Red Imported Fire Ant worker

At the time it was not clear to me if all the oothecae I had collected produces wasps, or if only a few did. Around a week later all of the wasps had expired, but there were still no mantises. It was beginning to look like there would be no mantises after all. I was very close to giving up and disposing of the egg cases and wasp remains, but I talked myself into holding off just a few more days. And fortuitously, just a day later, I was rewarded with the emergence of a mess of tiny brown mantis nymphs.

This juvenile mantis is just a little larger than the adult wasp parasite

All of the mantis nymphs were released into our landscaping on the first warm, sunny day after they emerged. Now it was time for a closer looks at the oothecae to see if the details of what had occurred could be wrung out. Right away I noticed that some of the oothecae had small holes on their sides, and some didn’t. As near as I can tell from my research, mantis nymphs emerge from the ridge at the top of the egg case—along the spine of the ootheca. Conversely, the holes located on the sides of the egg cases appear to be where the adult Podagrion wasp exited the ootheca.

So, there you go! I hope we all learned something new!

Are there any parasitoid wasps that lay eggs in the ootheca of the invasive Chinese mantis Tenodera sinensis in North America ?