I recently did a book review on Darwin Comes to Town by Menno Schilthuizen. This interesting book explores the possibility that the activities of humankind–and in particular urban development–is influencing and driving evolution in some of the species that frequent our cities. Schilthuizen refers to the concept as Human Induced Rapid Evolutionary Change, or HIREC for short.

BOOK REVIEW – Darwin Comes to Town by Menno Schilthuizen

In this book the author examines case after case of wildlife species adapting to the challenges and tribulations of urban living. But there were a couple of stories in particular that stuck with me after I had finished reading. On page 57 the author references an ongoing study of Coyotes centered in Chicago and Cook County. The researcher–Stanley Gehrt–noted occasions when he had seen urban Coyotes waiting for traffic lights to change before attempting street crossings. In other words, the Coyotes had learned how to better manage the challenge of urban automobile traffic.

A few chapters later, the author shares a story about stray dogs in Santiago, Chile looking both ways before attempting to cross busy city streets. Again, the dogs are demonstrating a learned behavior that helped them overcome one of the primary difficulties encountered by animals attempting to survive in an urban environment.

These two passages reminded me of a set of informal observations I had made in my own suburban neighborhood. We moved in to our newly developed subdivision in the early 2000s, and right away we noticed that there was a healthy population of both Eastern Cottontails and Fox Squirrel sharing the subdivision with us. It was a rare day when we drove along our street and did not notice a grazing rabbit or a tree hopping squirrel. Regrettably, we also noted an abundance of roadkill individuals of both species. Clearly both the Eastern Cottontails and the Fox Squirrels were having difficulty coping with the steadily increasing traffic on the streets of our growing community.

Fortunately, rabbits and squirrels are prodigious breeders, and the roadkill carnage did little to shrink their numbers. Even today–twenty years later–we still have plenty of Fox Squirrels and Eastern Cottontails frolicking in our front yards. But more than that, I can happily report that at some time in the interim, the number of cottontails and squirrels being lost to traffic appears to have dropped precipitously. These days it is a unusual occurrence when I notice roadkill on our neighborhood streets. Apparently, in the intervening years, our squirrels and rabbits have become better at dealing with the challenge of speeding automobiles than they were when our neighborhood was in its youth.

So, what could have changed over the course of just twenty or so generations to make such a noticeable difference for these small mammals? I can think of a few possibilities… Maybe–as with the Coyotes and Dogs mentioned earlier–the squirrels and rabbits simply learned how to better manage their interactions with traffic. If so, the lessons would have to be learned quickly, and with little trial and error. Maybe individuals were able to develop techniques for avoiding speeding automobiles by watching how other squirrels and rabbits managed similar situations. Maybe parents offered their youngsters lessons in the same. Some combination of these three possibilities is almost certainly how the Dog and Coyotes developed their impressive traffic coping skills.

But rabbits and squirrels are not canines. While squirrels in particularly can demonstrate a very entertaining level of intelligence, neither of these two small mammals are as capable in that department as Dogs or Coyotes. Further, rabbits and squirrels have decidedly short lifespans, with around two year being a ripe old age for both species. That doesn’t give them much time to learn new lessons. Neither species is very social, either–certainly not in the same ways canines are. It doesn’t seem likely that they are spending a lot of time teaching and/or leaning from each other. And, also unlike canines, both Eastern Cottontails and Fox Squirrels become independent at a very young age. There is not typically a lot of parental instruction that transpires.

So, learning new behaviors does not seem like a strong contender explanation for how our population of rabbits and squirrels improved their outcomes verses our neighborhood automobile traffic. Something else must be responsible for the reduced carnage, and I can think of a few possibilities…

- The people in our neighborhood have become more conscientious drivers, and now actively watch for wayward squirrels and rabbits to avoid hitting them.

- Native scavengers such as vultures and Coyotes have learned to access the bounty of roadkill, and they consume any resulting carcasses so quickly that there isn’t time to notice them.

- People–in some capacity–either public or private–are taking the initiative to clean up any roadkill in a timely fashion.

- The rabbits and squirrels have evolved behavioral adaptations that better equip them to deal with the challenges posed by automobile traffic.

All four of these options seem possible–some more so than others. And certainly there may be other possibilities that have not yet occurred to me.

Of these options, its the fourth one I want to explore further in this article, as the possibility that the squirrels and rabbits have evolved a solution to this problem segues well with the concepts explored in the book, Darwin Comes to Town. Just like with people, animals also present a full spectrum of possible skills and competencies within a certain range. Some individual animals of a given species will be good at some things, and some are talented in other areas. Some squirrels are bold, while others are indecisive. Some rabbits are born cautious, while others can be inclined toward recklessness. If we assume that these traits are inheritable, that leads to some interesting possibilities. Critters that are successful at managing the traffic problem will be alive to pass their beneficial traits on to their offspring, while those animals which failed the test will not.

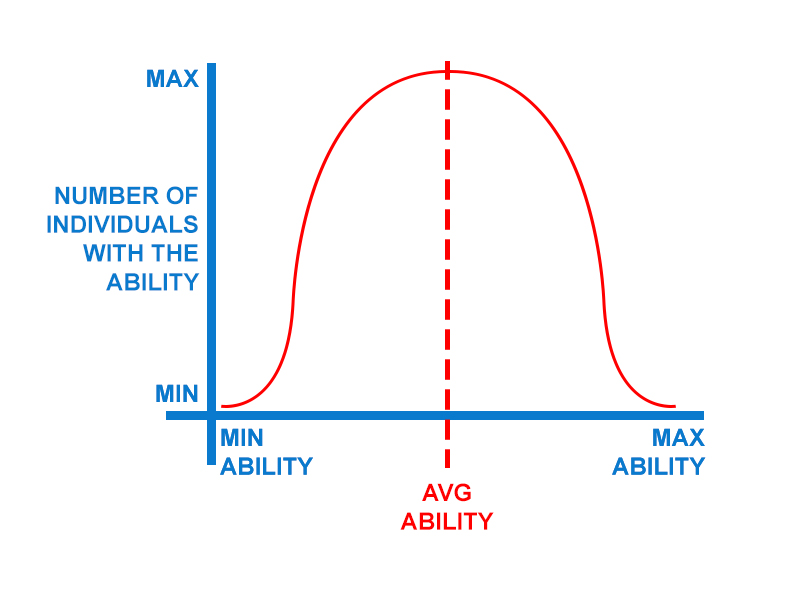

At any given moment in time a set of behavioral traits expressed in a population of individuals can be expected to fall out in the form of a bell curve. A small number of individuals will have a dearth of this ability, and a few will be very talented, while most in the population will fall somewhere in the middle. By definition, average ability will be the most common outcome.

The behavioral traits required by rabbits and squirrels to deal with the challenges posed by automobile traffic surely already existed–to one degree or the other–in our resident population. Maybe it was some fortuitous combination of boldness and caution. A skilled animal might be cautious enough to remain wary of oncoming vehicles, but decisive enough to cross the road quickly when the coast was clear. Some individual were surely capable of solving this problem well, while other always made the wrong decisions. Meanwhile, most of the populations had mixed results–they got it right sometimes and got it wrong others. See the graph below…

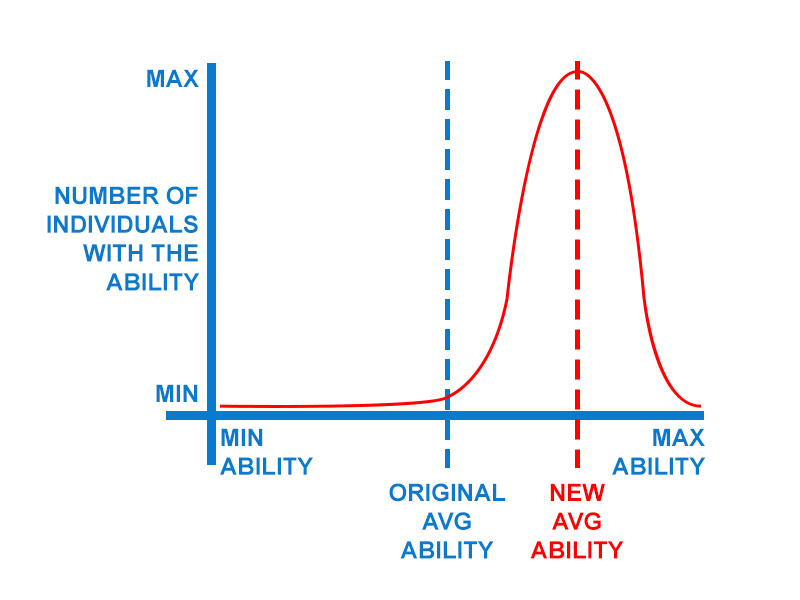

Now imagine that in just a matter of months most of the critters on the left side of this graph were suddenly removed from the population. The resulting situation might then eventually settle out to look something like what is illustrated in the graph below. Almost overnight the bulk of the regional populations would be dominated by individuals that are the best equipped to successfully manage the problems presented by automobile traffic. And if this skill was an inheritable trait, then it would be passed on to their offspring as well.

It is important to remember that everything I have presented in the article about the rabbit and squirrel population in our neighborhood is anecdotal. To verify that what I believed I observed was actually what was happening would require a well thought out and well executed scientific study (or series of studies). The first step of such a study would certainly be to find another appropriate new neighborhood (or multiple neighborhoods) in which to do the research. Our neighborhood was unique in that the construction site was surrounded by areas that promoted the influx of squirrels and rabbits. This population of small mammals was further facilitated by the fact that our home owner’s association requires the installation of landscaping and a certain number of trees in both our front and back yards. Many of the HOA sponsored tree species were mast bearing, providing plenty of food, while the ample landscaping served as cover and refuge for our furry friends.

Next would come a set of scientific studies to verify that the perceived positive changes in mortality actually were occurring. A thorough census would be required to get a good estimate of the number of squirrels and rabbits living in the neighborhood. This number would need to be checked and updated frequently. Roadkill would need to be carefully monitored in order to record an accurate count of fatalities over time. Carcasses or tissue samples might be put on ice for later study. And finally, an ambitious researcher might attempt to identify genetic differences between the early population compared to that of a later more competent gene pool.

How cool would it be to demonstrate that in prolific reproducers like rabbits and squirrels meaningful and demonstrable evolutionary change can take place in just a few generations, even in a place as pedestrian as an ordinary residential subdivision?