Dateline – Summer 2022 – North Denton County

Earlier in the summer I began to explore in—what for me was—a new area of the urban Trinity River bottomlands. Many of the places we scouted at this time were best accessed from the river via a kayak or canoe. Some were only accessible in this manner. These were very remote sections of the Trinity River forests, rarely visited by people, despite being surrounded by a populous multitude only a short distance away in every direction.

The extended drought in North Texas aided our explorations by lowering the river level and exposing more of the shoreline along the bottomland waterways . Gently sloped mudflats provided kayak takeouts that would have been much more difficult otherwise. The drought conditions also had the effect of retarding vegetation growth throughout, and especially in margin areas. This made many locations decidedly more passable than they would have been ordinarily.

Every spot we scouted showed signs of abundant urban wildlife, and it wasn’t long before we crossed paths with some roving critters. One of our first encounters was a trio of very young Armadillos exploring away from their den for what was possibly the very first time. We heard their rummaging some time before we sighted them, but telltale movements in the vegetation quickly gave away the position of the little Armadillos. The group was foraging in a growth of poison ivy just off the beaten path. We paused for a moment to watch their antics.

Armadillos do not have great situational awareness. Their eyesight and hearing appear to be poor. And they are often very preoccupied by their habit of rooting through the forest floor detritus in search of insects and other invertebrates to eat. Their armored plating gives them a certain degree of protection, and Armadillos seem to invest much trust in it to keep them safe from harm. Thus protected, Armadillos go about their business with seemingly little concern for their safety. The result is, that when encountered, Armadillos will often let you approach very closely—if you move slowly and keep the noise you make to a minimum. That was certainly the case with the three Armadillos in the video above!

A few weeks later we returned to the same neck of the woods and made a startling discovery as we stepped out of our kayaks. There among the sprouting vegetation coming up along the newly exposed mudflats was a deceased juvenile Armadillo. Based on the state of the carcass it would appear that the little Armadillo had passed away at this spot on the beach just an hour or two before we arrived. And judging from the size of this critter, it seems possible—if not likely—that this was one of the trio we had encountered on our first visit. The age was right, and so was the location—only around 20 yards from where the video had been recorded.

The dead Armadillo had clearly been mortally wounded. Blood could be seen around its snout and seeping from two puncture wounds to the Armadillo’s shoulder armor. But otherwise the animal was fully intact. For some reason whatever killed the Armadillo did not also consumed it. So what happened here? Was there enough evidence left behind to at least speculate about what did in this unfortunate little Armadillo?

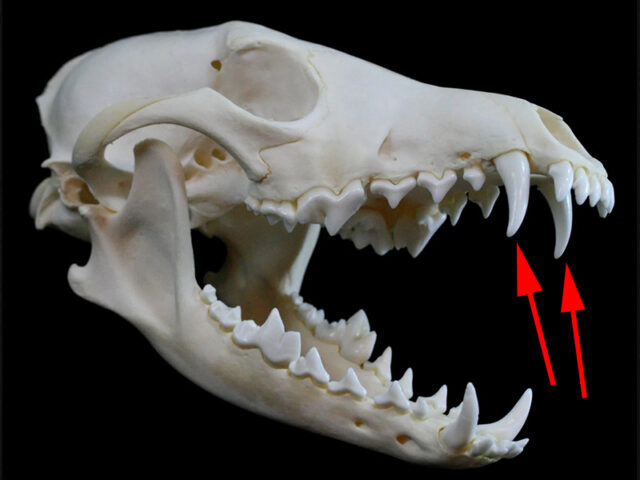

The first clue is perhaps the most obvious one—the puncture wounds on the Armadillo’s shoulder plate. These two injuries are just the right size and configuration to suggest that they were made by a pair of large, sharp canine teeth. More specifically, it can be judged that this injury was caused by the bite of medium-sized canine—either a dog or a Coyote. Our trail camera surveys in the area only recorded pictures of Coyotes. No dogs were photographed, making a Coyotes the most likely culprit.

An Armadillo’s armor is effective protection. The plate that wraps over the front part of their torso is meant to protect the animal’s neck, spine, and shoulders. If this had been an adult Armadillo it is unlikely that the attacker would have been able to open its mouth wide enough—or clamp down hard enough—to deliver a severe injury. But because this particularly juvenile Armadillo was still relatively small, the attacker was able to apply a substantial bite to the shoulder/neck area despite the armor plating. The result was significant injury to the Armadillo—but not one that was immediately fatal. It is likely that the Armadillo was still able to thrash, squirm, and uses it sharp claws to effect an escape. Once on the ground, the Armadillo surely made his way to someplace safe before the predator could re-engage—Armadillos can be quite quick when they need to be.

There was no sign of a struggle near the body of the Armadillo. No canine tracks on the soft soil of the beach. That suggests that the attack did not take place at the spot where the carcass was found. Instead the Armadillo had likely made his way to the shore some time after the Coyote had given up the chase and moved on. By the time the Armadillo wandered to the water’s edge, the severity of his injuries finally caught up with him and he could go no further.

For Coyotes, not every hunt is successful—not even for a well seasoned hunter. And it seems that Armadillos may be a particularly tricky prey animal to subdue. I’ve recorded instances of Coyotes having similar difficulties with Armadillos in the past. The Armadillo’s armored plate ain’t just for looks—it actually works! Refer to the trail camera sequence below which illustrates a Coyote briefly capturing, and then promptly losing, an adult Armadillo.

of the camera, and the Armadillo has escaped

It’s even possible that experienced Coyotes understand that there is a degree of frivolousness involved in efforts to subdue Armadillos. On more than one occasion my trail cameras have recorded images of the two animals in close proximity without concern from one, and without animosity from the other.

So, if Coyote do not regularly prey on Armadillos, what do they eat? Well, Coyotes are certainly opportunistic predators. What that means is, they will hunt and kill anything that they are able to. Life in the wild is too difficult to pass up a meal, and Coyotes will attempt a kill anytime they believe the have a reasonable chance for success. But hunts can be energy intensive, and even dangerous. There has to be a good likelihood for a positive outcome before it will be worth the effort for a Coyote to make the effort.

On at least one occasion my trail camera has recorded images of Coyotes hunting an opossum, but the outcome of the effort is not clear. See the pictures below. As horrific as this attack appears at first, follow up photographs taken in subsequent days seemed to show that the big male Opossum survived this encounter, little worse for the wear.

He may have a slight injury on his left shoulder, but it is difficult to be certain

I’ve seen evidence that Coyotes prey on animals as small as rats and mice, all the way to something as large as a 60 pound Beaver. I’ve seen them feeding on roadkill deer, and I have heard anecdotal accounts of them killing livestock—sheep, goats, and even calves. Most frequently, my trail cameras have recorded pictures of Coyotes with juvenile Raccoon kills. Young Raccoons are small enough to be vulnerable to predation, while at the same time being large enough to provide a substantial meal for a hungry Coyote.

The diet of Coyotes is not just limited to what they can catch, however. Coyotes are omnivores, and they will regularly feed on vegetable matter when it is readily available. Fruit is a favorite. Whenever I am surveying a new area and want to get Coyotes in front of a trail camera, apples are my lure of choice. Coyotes love them.

Wild Coyotes will often augment their diet with vegetable matter. At certain times of the years—and under certain conditions—they will switch to it almost entirely. In mid to late summer it is not uncommon for Coyotes in the DFW area to feed almost exclusively on Mesquite and/or Honey Locust beans. They may even feed on Osage Oranges. The change in diet is easy to observe by noting the contents of their droppings. Starting in mid summer a Coyote’s scat will often be found full of beans from one or the other of these plants.

Later in the season you might observe another change. Starting in September and lasting up until the first cold spell of autumn, Coyotes will switch their diets to easy to catch and abundant Differential Grasshoppers. Loaded with protein, these insect are a great supplement to a Coyote’s normal diet—A change in their eating habits that that is confirmed by droppings packed full of undigested grasshopper exoskeletons.

During the winter months an observant naturalist will notice another change to Coyote scat. Now, instead of beans and grasshoppers, Coyote scat will contain large amounts of animal fur—and indication that the Coyotes are once again relying primarily on hunting to meet their nutritional needs.

Great post. In Chicago area my trails cams picked up a few instances of coyote vs possum, the possums left the encounter intact.