October 2016 – Dallas County

During the summer and fall of 2016 I spent most weekends in the Great Trinity Forest. It was a remarkable 4 or 5 months. Each visit to the wilderness in the Trinity River bottoms presented a new visage as the effects of the changing season reshuffled the ecological deck. Bodies of water filled with the rains, and then evaporated with the coming of the intense summer heat. Vegetation grew up and died off. Animals—both common and uncommon—moved in to take advantage of the changes where they could, and moved on again when the bounty altered.

The mix of wildlife in the Great Trinity Forest is as rich as can be found anywhere in the state. Every weekend my friends and I were treated to distinctly new and amazing natural wonders. The show was truly spectacular. It never disappointed.

Our usual m.o. was to arrive at the crack of dawn and enter the woods at first light. On each trip to the Great Trinity Forest we would arrive with a specific objective in mind. But we only held onto our plans with a loose grip, so that we could adjust quickly to unexpected developments. The Trinity River bottoms will throw you wildlife curve balls. It pays to be accommodating.

On this beautiful, cool, and foggy early autumn morning we started the day by noting huge flocks of American White Pelicans following the Trinity River to the north. Wave after wave of the large white birds flew by heading for some unspecified location in the interior. It was beautiful to see and we watched for as long as we could.

But, we had an appointment with our agenda, and we needed to get moving. We followed the trail to the edge of the woods and then pushed through. When we emerged on the other side, this is the sight we were treated to. Dozens and dozens of Great White Pelican circling in for a landing on this lake hidden away deep in the heart of the Great Trinity Forest.

The shallow lake had nearly evaporated away over the course of the long hot summer, but there was still enough water here to provide for this huge flock of pelicans. The shrinking waters concentrated the lake’s fish in the small, shallow pools that remained. The situation provided an easy fishing bounty for the big birds. The pelicans were here to feast.

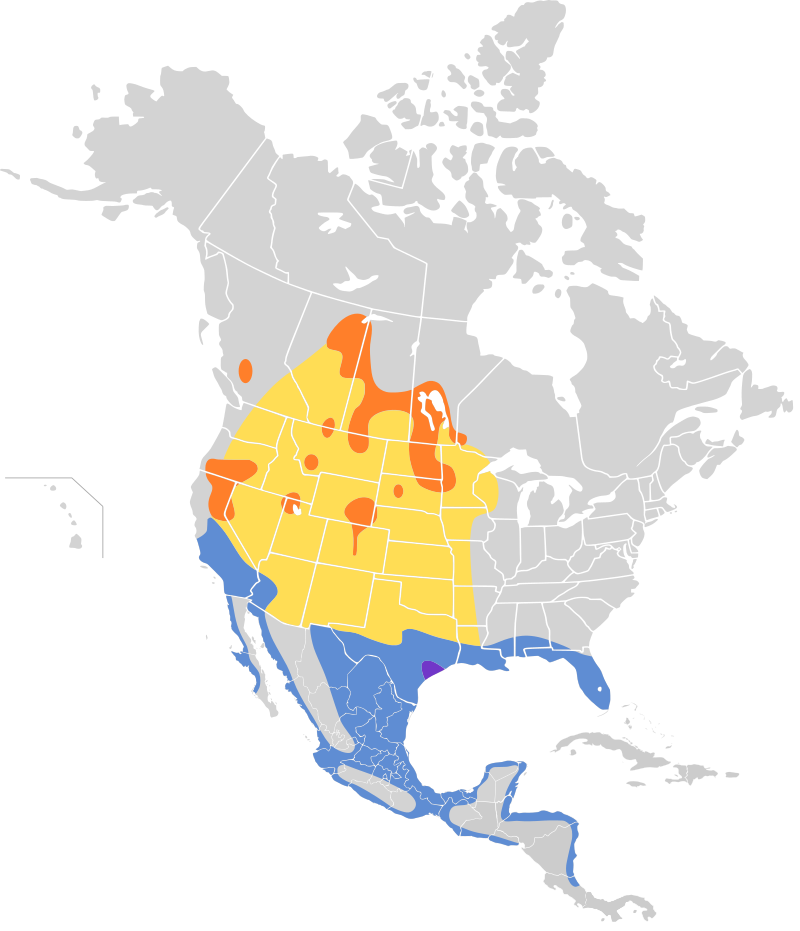

American White Pelicans are one of the largest birds in North America. Their 9 foot wingspan is surpassed only by the California Condor. Pelicans spend their summers on breeding grounds in the northern reaches of the continent’s interior. When the weather turns cooler with the coming of fall, huge flocks make their way south for the winter. Many spend their winters right here in the Dallas/Fort Worth Metroplex.

Here is how Wikipedia describes the behavior of these magnificent birds…

The American White Pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) is a large aquatic soaring bird from the order Pelecaniformes. It breeds in interior North America, moving south and to the coasts, as far as Central America and South America, in winter.

American white pelicans nest in colonies of several hundred pairs on islands in remote brackish and freshwaterlakes of inland North America. The most northerly nesting colony can be found on islands in the rapids of the Slave River between Fort Fitzgerald, Alberta, and Fort Smith, Northwest Territories. Several groups have been visiting the Useless Bay bird sanctuary since 2015. About 10–20% of the population uses Gunnison Island in the Great Basin’s Great Salt Lake as a nesting ground. The southernmost colonies are in southwestern Ontario and northeastern California. Nesting colonies exist as far south as Albany County in southern Wyoming.

They winter on the Pacific and Gulf of Mexico coasts from central California and Florida south to Panama, and along the Mississippi River at least as far north as St. Louis, Missouri. In winter quarters, they are rarely found on the open seashore, preferring estuaries and lakes. They cross deserts and mountains but avoid the open ocean on migration. But stray birds, often blown off course by hurricanes, have been seen in the Caribbean. In Colombianterritory it has been recorded first on February 22, 1997, on the San Andrés Island, where they might have been swept by Hurricane Marco which passed nearby in November 1996. Since then, there have also been a few observations likely to pertain to this species on the South American mainland, e.g. at Calamar.

Wild American white pelicans may live for more than 16 years. In captivity, the record lifespan stands at over 34 years.

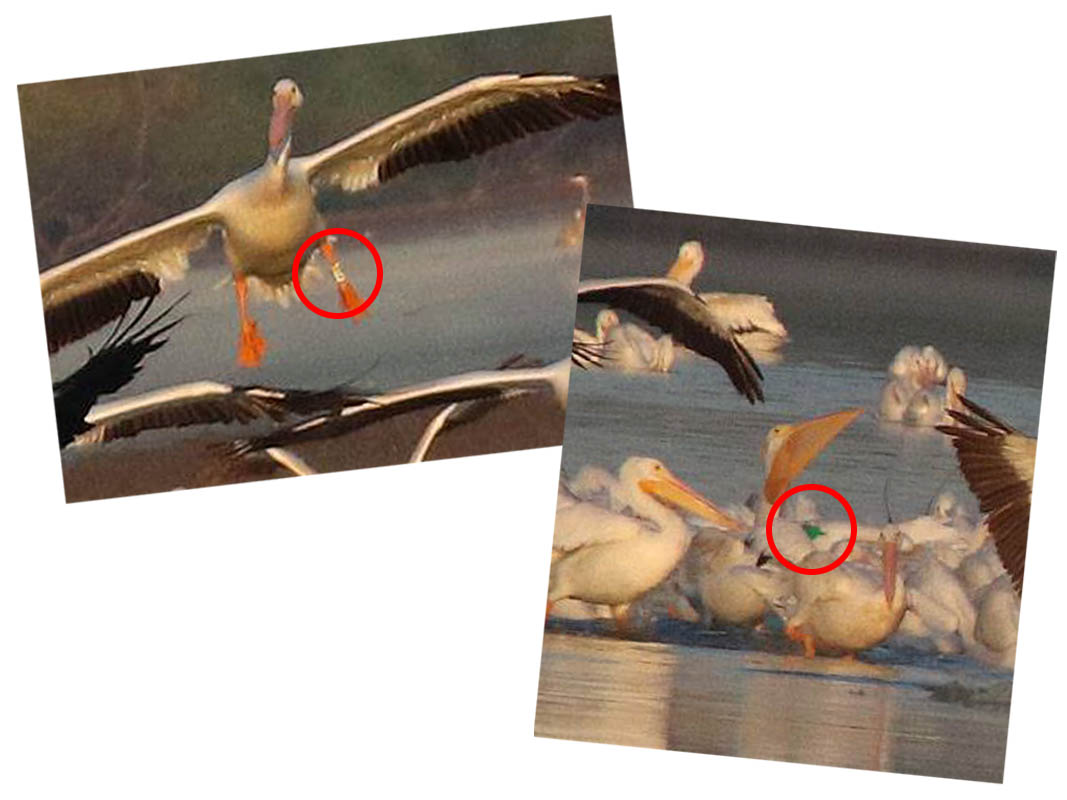

Several of the pelicans in this group were banded—some on legs and some on wings. In this case I was never able to clearly resolve the text on a band, but if I had been able to, there is a place to report it. For future reference, if any of you do spot a banded pelican (or other migratory bird) stop by the USGS website for reporting banded birds and drop them a line. Within a few weeks they will respond with an email containing interesting life history information about the bird you observed.

Here is and example from a similar report I filed regarding a tagged Snow Goose I observed last February. Of note here is the distance this Snow Goose traveled to reach the metroplex… All the way from the Arctic circle. The same kind of interesting data would be provided with a report submitted for an American White Pelican.

Also in attendance this morning was a small contingent of American Avocets. These dainty and attractive little birds were sharing the shallow waters with the Pelicans, and doing their best to stay out of the way.

Here is what Wikipedia has to say about the unique and interesting American Avocet…

The American avocet (Recurvirostra americana) is a large wader in the avocet and stilt family, Recurvirostridae. This avocet spends much of its time foraging in shallow water or on mud flats, often sweeping its bill from side to side in water as it seeks its crustacean and insect prey.

The American avocet measures 40–51 cm (16–20 in) in length, has a wingspan of 68–76 cm (27–30 in) and weighs 275–420 g (9.7–14.8 oz). The bill is black, pointed, and curved slightly upwards towards the tip. It is long, surpassing twice the length of the avocet’s small, rounded head. Like many waders, the avocet has long, slender legs and slightly webbed feet. The legs are a pastel grey-blue, giving it its colloquial name, blue shanks. The plumage is black and white on the back, with white on the underbelly. During the breeding season, the plumage is brassy orange on the head and neck, continuing somewhat down to the breast. After the breeding season, these bright feathers are swapped out for white and grey ones. The avocet commonly preens its feathers – this is considered to be a comfort movement.

American avocets were previously found across most of the United States until extirpated from the East Coast. The breeding habitat consists of marshes, beaches, prairie ponds, and shallow lakes in the mid-west, as far north as southern Canada. These breeding grounds are largely in areas just east of the rocky mountains including parts of Alberta, Saskatchewan, Montana, Idaho, Washington, Utah, North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Colorado, and even down to parts of New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas. Their migration route lands them in almost every state in the western United States. The avocet’s wintering grounds are mainly coastal. Along the Atlantic Ocean, they are found in North and South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. There are also wintering grounds along the Gulf of Mexico in Florida, Texas, and Mexico, and along the Pacific Ocean in California and Mexico. There are resident populations in the Mexican States of Zacatecas, San Luis Potosi, Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Mexico City and Puebla, and in Central California.

American avocets breed in anything from freshwater to hypersaline wetlands in the western and mid-west United States. American avocets form breeding colonies numbering in dozens of pairs. Throughout the breeding season, birds pair off in a series of copulatory displays. After breeding, the birds gather in large flocks, sometimes amounting to hundreds of birds. Nesting takes place near water, usually on small islands or mucky shorelines where access by predators is difficult. Together, the male and female build a saucer-shaped nest, take turns incubating the four eggs, and tending to the precocial young. Upon hatching, the chicks feed themselves; they are never fed by their parents.

Another great report, Chris. The avocet photos are particularly nice. Thanks for doing these reports, I always enjoy them.

Great shootin Chris thanks

Where is the best place to start exploring the Trinity River area in Dallas? Thank you