DATELINE – May 2022 thru January 2024

In the summer of 2022 my trail cameras began recording pictures of a White-tailed Deer sporting a strangle-looking set of antlers. Early on, the developing antlers consisted of a particularly large-diameter base with multiple velvet-covered tines, each sprouting in oddly twisting and turning directions. As the antler growth continued on through the season, so too did the peculiar nature of their appearance.

As summer transformed into fall, the strange antlers reached their maximum length, and the velvet was shed soon afterwards. The atypical tines writhed up from the base, pointing in many different and unusual directions. It was at this point that deer earned the nickname, Medusa–for obvious reasons.

Medusa continued to show up in front of my camera off and on through early December, and then the oddly-antlered deer abruptly disappeared. In its place came another deer with a different, but equally bizarre looking, set of antlers. This deer was photographed in the same locations, and by the same cameras that had been snapping photos of Medusa just a few weeks earlier. Somehow we never managed to record pictures of the two unusual deer together.

The antlers on this new deer also had a nice wide base–just like Medusa’s–but instead of spiraling tines, this deer had short, stubby antlers. This was not a spike buck, though, this was something entirely different. We named this new deer, Knobby–again for obvious reasons.

In addition to being short and broad, Knobby’s antlers were also raw and appeared damaged in those early photographs. In some ways they looked as if they were in the process of shedding their velvet, but the timing was way off. White-tailed Deer ordinarily shed the velvet from their antlers much earlier–in late summer or fall–not mid-January. I was very puzzled by this new development.

I posted a few pictures of Knobby to our associated Facebook page to see how folks would respond to them. Several of our followers made the suggestion that Knobby could be an antlered doe, but from my research, Knobby did not fit the profile. Female deer with antlers will usually have short, skinny, and unbranched antlers. Their antlers will normally retain their velvet covering. Further, antlered females do not ordinarily drop their antlers annually the way bucks do. See the picture below for an example of a typical antlered doe…

Photograph from FishGame.com

But Knobby also showed an inclination to congregate with groups of does. I felt like that was out of character for a buck at this time of year, and wonder if this behavior might be evidence that Knobby was a female deer after all. Mostly, I remained unsure.

Knobby continued to show up in photographs through the end of January 2023, and then he too abruptly disappeared. At the time, I made a mental note concerning the oddity of these two deer, but I didn’t think too much of it otherwise. Atypical antlers are not unusual in this part of the forest, and I was inclined to simply write this pair off as slightly more extreme variations on the expected.

These two deer did not cross my mind again until Medusa started showing up in front of the camera again the following summer, around mid-July 2023. This time Medusa sported an even larger and more elaborately twisted set of antlers than before. So strange were these antler, I once again decided to post a few pictures to our Facebook page to see what the reaction would be.

In general, the response on Facebook was everything I had hoped it would be–and more. A few people chimed in with the suggestion that this deer might be kind of special. Again some folks proffered the idea that Medusa might be a antlered doe. Others suggested that Medusa could be a hermaphrodite. Both possibilities piqued my interest, and I decided to once more do a little digging on the internet to see what I could find out.

After hitting Google with a few carefully crafted queries, it soon became clear that cause of these weird antlers was almost certainly a hormonal issue–likely low testosterone. But once again this deer did not fit the description of an antler doe–for the same reasons mentioned above. A hermaphrodite also seemed unlikely–from what I found on the internet, hermaphrodite deer are extremely rare. There were other possibilities–including a condition known as cryptorchidism. But, regardless of how much I researched, I still could not close on a satisfactory answer. I remained undecided on the best explanation for Medusa’s unusual appearance.

During the fall of 2023 my trail cameras continued to record pictures of Medusa on a fairly regular basis. Notably, in all this time, I never recorded one picture of Knobby. This was the second year in a row that the two deer were not photographed in the same area at the same time of the year. This struck me as strange. Both deer shared the same woods, but for some reason Knobby was not present in the fall and early winter. I wondered if Medusa would again disappear if and when Knobby returned in January.

Then in early November I had the good fortune to record a nice close up of Medusa’s antlers. They were in terrible shape. Medusa’s antlers appeared broken and bleeding in this photograph, as if they were in the process of crumbling and falling apart. With this clue I began to suspect that maybe Medusa and Knobby were somehow the SAME animal. I decided to do a little more research.

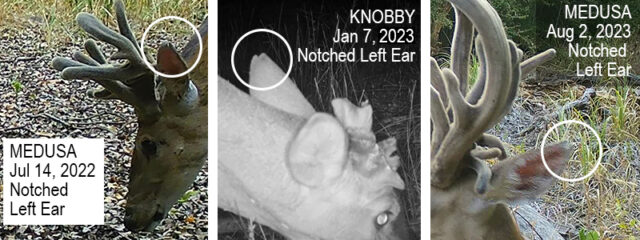

I started by going back to my archive of pictures to collect as many pictures of Knobby and Medusa as I could find. Afterwards I reviewed the pictures looking for similarities in form or appearance that might support the idea that these two were the same deer. I started off by comparing body size and dimensions. The match looked good to me, but I found no distinguishing characteristic that would cement the ID.

Then I noticed a distinctive notch at the tip of Medusa’s left ear. Quickly I searched through my photos of Knobby, and it only took a moment to locate a picture that confirmed that Knobby too had a notched left ear! Pretty strong evidence that these two strange White-tailed Deer were one in the same! Now I needed to find an explanation that would account for the drastic change in the appearance of the antlers.

As December progressed, Medusa again became camera shy, and we stopped recording pictures of him–just as had been the case the year before. And then toward the end of January 2024–again just like in the previous season–Knobby started showing up in front of my trail cameras, right on cue! But, this time Knobby, was not fully knobbified. Instead, Knobby was in some intermediary stage, with at least one of Medusa’s curly tines still present! Now I was sure these two were the same deer!

But how was this possible? I had never heard of deer sporting antlers that would crumble away well before the normal time for the annual shed. And I still had plenty of questions about why the antlers developed in this unusual way to begin with. Ordinary atypical and asymmetrical antlers can result from injuries or nutritional deficiencies, but these atypical antlers were atypical, atypical antlers! There was definitely something else at work here.

I discussed the pictures and my finding with associates, and when we still couldn’t close on an answer, I decided to reach out to a White-tailed Deer expert at Texas A&M AgriLife Extension to see what they might have to add to the discussion. Here’s how they responded to the photos I sent…

I received the pictures, and that is a wild-looking deer or maybe a couple deer! The ear notch–and probability–make me think they are the same deer.

My immediate reaction is cryptorchidism, which is a birth defect that causes one or both testicles to remain in the abdominal cavity instead of descending into the scrotum. Due to this, the buck does not have normal testosterone production, which controls the annual antler cycle. Bucks with this condition do not shed or cast their antlers at normal times, if at all, and won’t typically have neck swelling or stained tarsal glands. They likely won’t exhibit normal rutting behavior. Cryptorchid bucks usually have crazy antlers, like the ones pictured, and they have giant antler bases. They are sometimes referred to as “cactus” bucks. An injury to the testicles can cause similar symptoms.

Hermaphrodite or pseudohermaphrodite (external genitalia of only one gender) is another possibility, but it is extremely rare. If so, you would expect similar symptoms to those I listed above.

Cryptorchidism can also keep antlers from hardening, so they remain brittle and can easily break. So, that’s probably what’s going on. Hard to tell without examining the deer.

Bucks will be in bachelor groups during spring and summer. They start to separate in the fall as testosterone increases, which is controlled by photoperiod (day length). But, a deer with testosterone issue may not behave normally because their testosterone does not fluctuate normally. I wouldn’t be surprised if a cryptorchid buck kept weird company.

Jacob Dykes, PhD, Assistant Professor, and Extension Wildlife Specialist

So, there you go! This is likely the best answer possibly short of somehow conducting a full, in-person medical examination–an unlikely proposition. In the meantime, I will continue to run trail cameras in these wood for at least the next couple of seasons. Hopefully we can continue to record pictures of this peculiar deer, allowing us to glean even more information about its unusual condition! White-tailed Deer oddities in the Dallas/Fort Worth area! How about that!