October 26, 2014 – Denton, Texas

This is part one of a two part series. After many years of looking with great interest at aerial photographs and maps of the area, I finally had an opportunity to explore the vast tracts of public wilderness just north of Lewisville Lake. This is one of the most expansive areas of bottomland in North Texas, and as such it calls out for exploration. Greenbelt Corridor Park, located on the eastern outskirts of Denton, Texas, is where we began this expedition.

With me on this trip was photographer, Phil Plank. From the beginning this trip was to be more about exploring than about wildlife photography, but we brought our cameras along nonetheless. At some point along the way I smeared my camera lens with some kind of viscous liquid, and many of my shots came out blurred because of it. That made me doubly glad to have Phil along to help me document the hike. His pictures will fill in many of the gaps in my own coverage.

Those of you who are regular readers of this feature know that I have something of a propensity for wandering away from well established trails. I am inclined to make any excuse I can to explore rarely traveled and seldom visited spots. This hike was to be no different.

The first stop on this hike was a small pond just a short distance from the parking area. By studying Google Maps it was clear that there was some kind of path that cut through the woods at least this far. We would use this pond as a staging area. From here we would try to size up the more ambitious aspects of our plans and determine whether we should give them a go or not. This would also be a good place to regroup in case a retreat became necessary.

Our intentions were to enter woods just past this pond and cut across the heart of the floodplain—visiting a few remote ponds and land forms along the way—before eventually arriving at a group of five small lakes located on the northeast corner of the property, just over a mile and a half away.

The only problem was that I had a very difficult time sizing up the up the terrain using Google Maps and Bing.com. I could tell that the vegetation was going to be very dense—in aerial photographs it resembles the dense fur of a Beaver pelt across most of the floodplain. What was not clear, is just what kind of vegetation this would be. If it turned out to be open field, it should be passable, even if the plants were shoulder high in places.

But no matter how hard I tried, I could not convince myself that this floodplain contained open fields. In North Texas there are certain bushes and trees that grow around in and near wetland areas. Branches on these plants radiate from a central point on the ground and form dense tangles with their neighboring bushes. Where these plants thrive, nearly impenetrable barriers can grow up.

I was afraid that was what we were going to be looking at here. I had never encountered more that small localized areas of this type of vegetation in the past. But, if that was what we were to find here, there would be acres and acres of it. A daunting prospect.

Tracks of Raccoons, Coyotes, and deer abounded on the shores of this pond, but small frogs—known as Blanchard’s Cricket Frogs—provided the preponderance of wildlife at this spot. Walking along the water’s edge, the ground in front of us came alive as dozens of these little amphibians leapt clear of our intended path. Back on the trail we encountered a much larger Southern Leopard Frog. This was good habitat for frogs.

The trail leading away from the pond was draped with oddly curved branches and tree trunks. After some deliberation, it was here that we decided to enter the woods and make our attempt to cross the floodplain. At first the going was not difficult. The branches were high and the ground was clear. We could snake our way through the woods walking upright.

But, the further we wandered from the trail the denser the vegetation grew. It soon became necessary for us to crouch in order to make our way past low hanging branches. We encountered a Feral Hog in here—medium sized and solid black in color. He fled as soon as he saw us. This was a perfect habitat for for these creatures, and the low branches left passable corridors that were just the right size for wild swine.

The strange, arching of the branches and trunks continued on as we made our way through the woods. All of the plants were leaning the same direction as if they had all been permanently bent by the same force at the same time. The vegetation grew thicker and lower to the ground in this region and progress became difficult and slow.

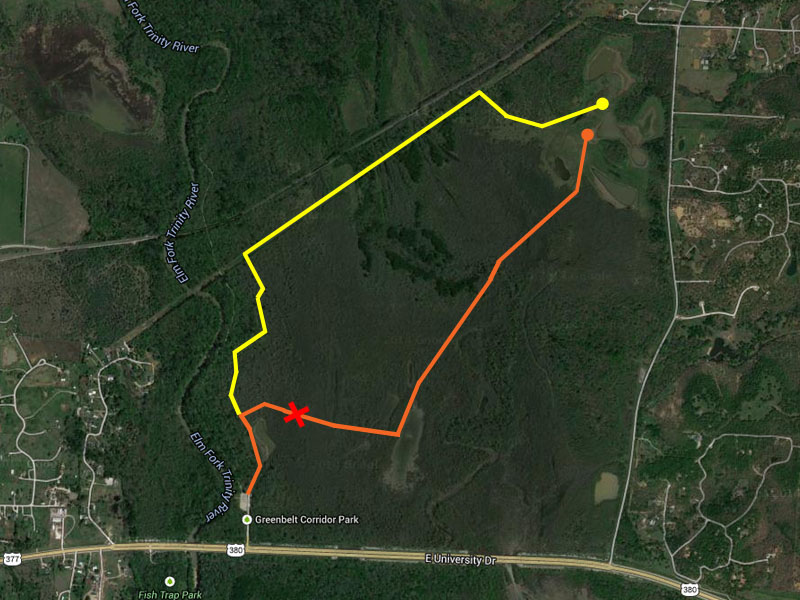

Our intended route is marked in orange on the aerial photograph below, but by the time we reached the location marked with a red “X” we had to concede that we had reached the end of the road.

We had hoped on several occasions that we were about to exit the thicket, but each time it was just a small clearing or momentary thinning of branches that we had found. About 400 yards to the east of where we started, and on our hands and knees, we made the decision that it was time to head back.

Reviewing our hike on aerial photographs later in the day, Phil commented that the place we made it to was, “the beginning of insanity.” I think that sums up the situation pretty well.

It is hard for me to imagine anyone getting through to the heart of this floodplain without a dedicated effort complete with chainsaws and bulldozers. The interior of this plain may very well be one of the most isolated areas in all of the metroplex. The mysterious ponds and lakes inside have probably not seen a human presence in quite some time. I’m sure they would be very interesting to visit.

With no other option left, Phil and I carefully retraced our steps back to the trail, and then followed it a little further north to the utility right of way we intend to use as our “Plan B.” From there we followed the path marked in yellow on the aerial above, with much better success. Following the power lines to the east allowed us to skirt the most impenetrable parts of the floodplain vegetation.

The transmission towers along this route were being used as roosts for dozens and dozens of the Black Vultures and Turkey Vultures. As the sun rose higher in the sky many of these vultures began sunning their wings—a technique these bird use to help sanitize their wing feathers. Feeding on carrion is a dirty business and steps must be taken to avoid disease.

Huge flocks of migrating Double-crested Cormorants passed overhead on several occasions during this leg of the hike. Each time it was a spectacular sight to see. These are our winter cormorants. In the summer the very similar looking Neotropic Cormorant is commonly observed in North Texas. In our colder months, Double-crested Cormorants are more likely to be seen.

A large female American Kestrel was observed hunting insects along the ROW in sections that had been vacated by the vultures. She would perch high on top of the towers to survey the relative clearing the right of way provided, and then swoop down to grab an unsuspecting grasshopper or dragonfly.

Eventually, we reached a portion of the right of way where the vegetation thinned a bit to the south, and we were again able to enter the woods. This was more of an upland forest and we were able to pass through easily. We soon emerged into the grassland area surrounding the five small lakes that were our goal for this hike.

The lakes are still holding water, but they have been hard hit by years of extended drought. All are reduced in size, and one is nearly completely dry. In spite of this, there was still much evidence of wildlife activity in the area. Deer and Coyote sign were easy to find. Insects of all types began to make their appearance as the mid-morning sun warmed the air. It was late October, but the temperature was scheduled to rise well into the 90s before the day was over—summer releases its grasp with some reluctance in North Texas.

On one pond we discovered a massing of Whiligig Beetles—a common sight in mid autumn. I’m not sure how to explain these fall congregations, but perhaps they are related to mating, or possibly the end of the larval stage occurs simultaneously for many of these insects. Here is what Wikipedia has to say about the Whirligig Beetle:

The whirligig beetles are a family (Gyrinidae) of water beetles that usually swim on the surface of the water if undisturbed, though they swim actively underwater when threatened. They get their common name from their habit of swimming rapidly in circles when alarmed, and are also notable for their divided eyes which are believed to enable them to see both above and below water. The family includes some 700 extant species worldwide, in 15 genera, plus a few fossil species. Most species are very similar in general appearance, though they vary in size from perhaps 3 mm to 18 mm in length. They tend to be flattened and rounded in cross section, in plan view as seen from above, and in longitudinal section. In fact their shape is a good first approximation to an ellipsoid, with legs and other appendages fitting closely into a streamlined surface.

The Gyrinidae are surface swimmers for preference. They are known for the bewildering and rapid gyrations in which they swim, and for their gregarious behavior. Most species also can fly well, even taking off from water if need be. The combination constitutes a survival strategy that helps them to avoid predation and take advantage of mating opportunities. In general the adults occupy areas where water flows steadily and not too fast, such as minor rapids and narrows in leisurely streams. Such places supply a good turnover of floating detritus or struggling insects or other small animals that have fallen in and float with the current.

The adult beetles carry a bubble of air trapped beneath their elytra. This allows them to dive and swim under well-oxygenated water for indefinite periods if necessary. The mechanism is sophisticated and amounts to a physical gill. In practice though, their ecological adaptation is for the adults to scavenge and hunt on the water surface, so they seldom stay down for long. The larvae have paired plumose tracheal gills on each of the first eight abdominal segments.

Generally Gyrinids lay their eggs under water, attached to water plants, typically in rows. Like the adults, the larvae are active predators, largely benthic inhabitants of the stream bed and aquatic plants. They have long thoracic legs with paired claws. Their mandibles are curved, pointed, and pierced with a sucking canal. In this they resemble the larvae of many other predatory water beetles, such as the Dytiscidae. Mature larvae pupate in a cocoon that also is attached to water plants.

We only had time to give this place the most abbreviated once over. Time was running short, so we looked around quickly before staring the long walk back to our cars. This is a very intriguing spot that demands further exploration. We will be back.

Chris, this sounds like a neat trip. I believe the shrub that blocked your travel is Buttonwood. It grows in standing water and is a common inhabitant of the back waters of reservoirs and also of ponds in North Texas.

Forty-five years ago, and at times since when water levels have been higher, the area to the east of the river where you were was generally inundated by Lake Lewisville (then called Garza-Little Elm Reservoir). I don’t think inundation has occurred since construction of Aubrey Dam.

If you stick with the Greenbelt trail, you eventually can come to what has often been called the Green Valley Bridge, an old iron bridge dating from around 1900 as the main crossing of Elm Fork between Denton and Aubrey. The bridge deck is long gone, probably removed for safety reasons. The road to it was never paved. It is decommissioned on the west side now I believe, and was on the east side long before the 1960s when I frequented the place. One could only reach the bridge by automobile when the road was dry, as it was just graded native Houston Clay.

I think the bridge had another official name, and that the location was a crossing dating from Republic of Texas days because there was hard bottom there. It is one of the few places on the Elm Fork in Denton County where hellgramites can be found because of the hard bottom. On the west bank at the road approach to the bridge there was the largest bur oak I have ever seen, with a trunk more than five feet in diameter.

You can find the bridge on Google Earth, and also photos on the Dallas History Phorum, where M.C. Toyer posted some photos a few years back.

When I was a graduate student at UNT, biology students there frequented the area, and several utilized the river at that location for field studies. My major professor Bill Pearson and I did some of the environmental impact studies for the Aubrey Dam on the river. At that time, Blue Suckers still occcurred in that stretch of the Elm Fork, but Aubrey Dam has eliminated them as they require long stretches of riverine conditions. Spotted Bass were also common in the river in that stretch, again the rocky bottom contributing to their preferred habitat.

A friend of mine collected both an Eastern Wood Rat and a Spotted Skunk near there for the mammalogy collection at UNT around 1970. I think both may still occur in the area. I observed wood rat nests the last time I was there in the mid-nineties. Both the skunk and the woodrat specimens were obtained on the east side of the river in dry oak woods.

Well, I was hoping you would chime in, David. I knew you would have some interesting insights about this area. I do intend to head further north on subsequent trips. I will make the old bridge a destination for sure. Part two of this article will cover my visit to the Clear Creek Natural Heritage Center on the west side of the river. It is quite a nice place as well.

Thank you for your ID on the vegetation we encountered. Do you have any thoughts on why all the branches seemed to be swept over in the same direction?

I will keep my eye open for both the spotted skunk and the eastern woodrat. I have a tentative ID on iNaturalist for an eastern woodrat which was observed in Farmers Branch. Maybe you can provide a positive ID… Here is the link if you would like to take a look: http://www.inaturalist.org/observations/830352

Thanks, David!

-Chris

Chris, I agree that the photo is most likely of an Eastern Woodrat, though lighting that would better show the fur color on the sides (generally not typical grizzled yellow agouti of wild rodents, but rather with warm brown tones in the gray) would help. Also, as I recall from live and preserved specimens, the demarcation between the very white underside and the warm brown/gray sides and dorsum is quite sharp, but that can’t be seen in these views.

The behavior of feeding in the foliage of a tree or shrub is reported in almost all references.

Given the location, I would wonder if there is a viable population. I have never seen the tell-tale stick mound against a tree or log in truly urban settings. If the riparian woodland is extensive along the creek there, then it seems more reasonable that there might be a population persisting. As I recall from my most recent visits to that area, the residences and manicured landscapes associated with businesses, churches, developed parks abut the creek pretty closely, but I may not remember correctly.

If you can get in touch with Earl Zimmerman, Professor Emeritus of Biological Sciences at UNT, he can positively identify any mammal you might run into from a photo. Unfortunately, I don’t have contact information at hand.

So far as the buttonwood, I am less sure of the identification after looking again, because buttonwood usually branches in a rosette from the base rather than having single trunk structure. However, some of the photographs do show typical appearing buttonwood. The lean of the apparently dead ones I would speculate occurred due to the same flowing high water that eventually deposited the silt that forms the ground there today when the water level dropped. My best guess, anyway.

I found Dr Zimmerman on Facebook… Here is what he had to say about the Wood Rat:

“I think the ID is correct. They are fairly common in the area. I have caught several in Denton, Co. over the past 40 years. They occur most often in bottomland forest, but can be found in any wooded or thicket areas. Nice photo. Glad to help.”